KATHERINE TAKPANNIE

Itiitiq | ᐃᑏᑎᖅ

Solo Exhibition

September 4 – October 5

Reception: Saturday September 21, 2 – 5pm

Olga Korper Gallery is pleased to present Katherine Takpannie’s second solo exhibition at the gallery.

In Inuit culture, a name carries weight.

We hold strong beliefs around how children are named and take great care in choosing a name for an infant. Traditionally, elders or parents named children, often after blood relatives, revered leaders or hunters, or exceptional people. We believe that a person never really dies, their spirit is passed on through our namesake tradition from which children receive their atiq, or “soul name”. Inuit naming traditions were not gender-specific; males could be named after females and vice versa, as well as, women did not take on their husband’s family name.

My grandmother, Tikishak Mikijuk Takpanie (E7-430) told my anaana (mother) Kunnuk Takpannie (E7-1615) to name me Itiitiq. Not only do Inuit believe spirits live on through the namesake tradition, but also children take on characteristics and personalities of namesakes. Therefore, I have taken on itiitiq’s traits. Recently, I have been learning more about Itiitiq. Itiitiq was a man who was adopted from Kuvianaqtuliaq to Harry Kilabuk. The elders of Apex Hill (a small community close to Iqaluit, Nunavut) still alive today, shared that Itiitiq was a very good man. He was a humble man. I was told that he was quiet and kind.

This exhibition is grounded in learning more about who I am. Unlearning the impacts of acculturation and further reconnecting deeply with myself and my heritage. Involving sharing creation stories told by Inuit since time immemorial, to ‘nirijunga’, which means “I am eating” -country food. Country food is a term used in Canada to describe traditional Inuit food, which includes marine life such as shellfish, whales, seals, and arctic char; birds and land animals such as ducks, ptarmigan, bird eggs, bears, muskox, and caribou; and plant life including roots and berries. Country food is an integral part of Inuit identity and culture, and contributes to self-sustainable communities.

Traditional stories:

Amarok – Amarok is the name of a gigantic wolf. It is said to hunt down and devour anyone foolish enough to hunt alone at night. Unlike real wolves who hunt in packs, Amarok hunts alone. Stories of Amarok have been shared from Greenland to Labrador, varying in different circumstances but all agreeing upon every principal point. Amarok has been known as a benevolent guardian, dangerous predator, or test of strength with a moral tendency, bringing before us the idea of a superior power protecting the helpless, and avenging mercilessness and cruelty. It was also known that Amarok would pick off sick caribou when the herds get too large. This helps the herds grow in strength and be better sources of food for the Inuit.

Tulugaq | ᑐᓗᒐᖅ | Raven – The Raven is a major figure in our creation story; being part Human and part Raven, and is seen with a raven’s beak. According to our oral traditional stories, the Raven made the world, brought light and was the creator of many landforms seen to this day, including mountains, rivers, and islands with beats of its wings. One day there was a raven flying through space and he thought to himself, “I’d sure like to rest. I’ve been flying for infinity, I’d really like a place to rest.” As soon as he thought that, snow began forming and collecting on the raven’s expansive wing until the raven’s wing tipped over, and was large enough for him to land on. But it was dark and cold.

The Raven then said to himself, “I have to have light. I need to see.” The raven began to tap its beak on the ground, where a plant with a light formation inside of it sprung from the ground. The raven grabbed the bright object from the plant and flung it to his side, becoming the sun. As soon as the sun had set later that evening, the raven again procured a plant with a fainter glowing bulb, and created the moon.

That is how the Raven created the universe.

Although the Raven created this world, the Raven was not thought of as a god. He was thought of as the transformer, the trickster. He was the being that changed things—sometimes quite by accident, sometimes on purpose.

It has been known that in the olden days, animals and humans spoke the same language. With the Raven being a poor hunter, (a scavenger with the reputation of the only animal that eats the feces of all the other animals) he would often help hunters locate other animals and in return, a hunter would share part of the catch.

On this day, Tulugaq was flying high in the sky, and led a hunter to a mountain. Once he arrived, Tulugaq caused an avalanche to fall, killing the hunter in order to feast off “his eyes”. Now, instead of being the creator of light, Tulugaq is now seen as the trickster, a catalyst of mayhem. Inuit learned that although Tulugaq was the creator, he did not do this for the good of the universe, but only for himself. They realized Tulugaq cannot be trusted and he is more selfish than generous.

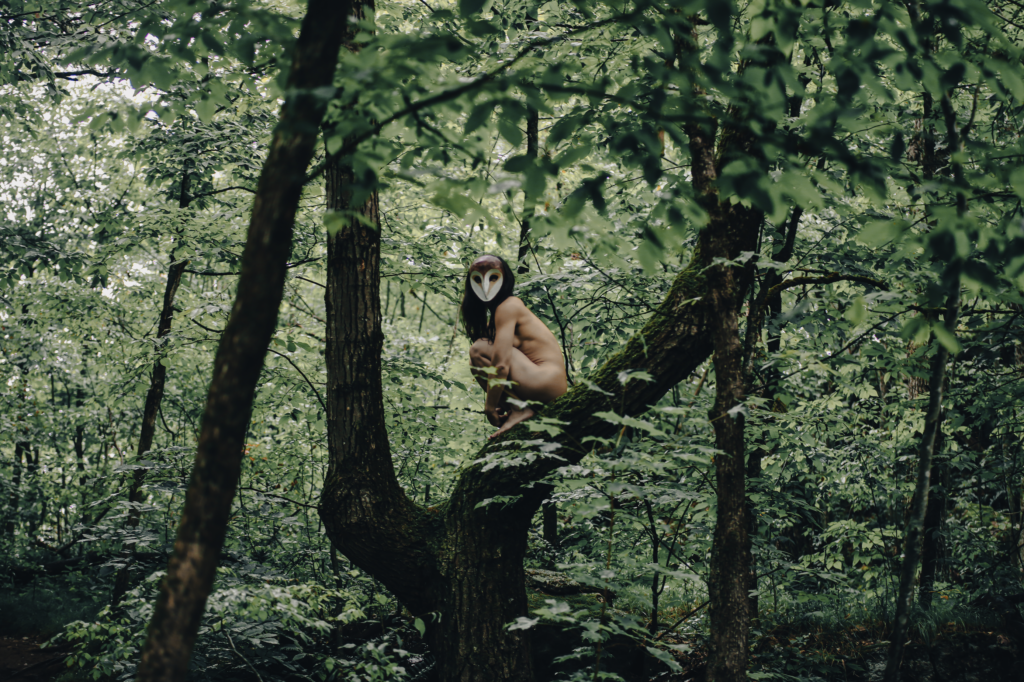

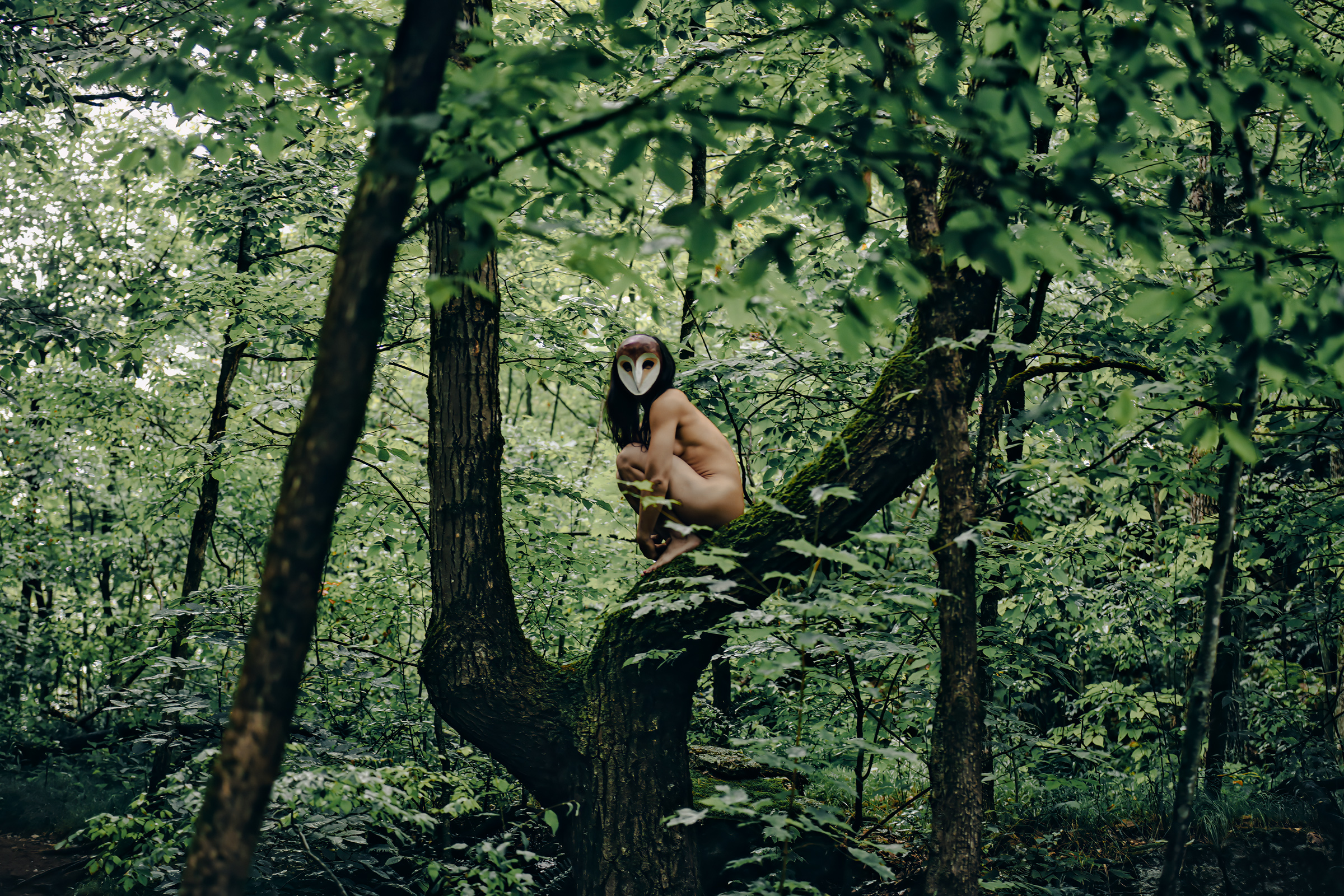

Ookpik | ᐅᒃᐱᒃ | Owl – The ookpik are intriguing birds of prey, that will also bring you joy. They are a source of guidance and wisdom, and will safely bring the spirits of the dead to the afterworld.

Sedna: From Greenland to Alaska, according to Inuit legend, Sedna is the Goddess of the Sea, the mother of all marine mammals. Sedna holds all of the sea animals entangled in her hair, only to release them when she is appeased by offerings, songs or a visit from an angakok (shaman), who combs the tangles from her hair.

Inuit follow tirigusuusiit; there were things that people had to do and things they had to refrain from for it was forbidden. Tirigusungniq had many purposes. Only by observing all these rules could Inuit maintain an order where animals would allow themselves to be killed or reborn. Animals were thought of to reincarnate continuously, and the same prey was always expected to return to a hunter who has shown its due respect: this was known as angiraaliniq. Thus hunter and prey were connected in a cycle of exchange. The hunter depended on the animal for survival, and the animal was brought back to life again by the rules of respect that the hunter and wife observed.

Sedna: On Thin Ice (Story concept created by Katherine Takpannie on climate change): Within Inuit cosmologies and epistemologies, uncertainty, unpredictability, and change are foundational. The world is understood to be ambiguous and to elude full comprehension and thus change is both expected and accepted. However, not changed by man. The term ‘climate change’ in Inuktut is ‘silaup asijjiqpallianinga,’ and it directly translates to “Sila being made to change.”

Inuit recognize that our homelands play a central role in regulating the Earth’s climate system. Our relationship with our environment has already been profoundly altered. We are deeply concerned about these impacts on our youth — their ability to safely engage in harvesting activities and to learn from our Elders about our way of life is increasingly compromised. Most of our Elders were born on the Land, and they have seen the creation of permanent settlements in their lifetimes. For us, sea ice is a fundamental source of food, learning, memories, knowledge and wisdom.

Sedna warns of the effects of climate change on the ecology of the Arctic are inextricably entwined with the lives of those who have lived on the land for thousands of years. For centuries, Inuit have maintained a close relationship with ice (siku), land (nuna), sky (qilak), and wildlife (uumajut). We have cared, respected and honoured all life.

Until, we couldn’t. Our new neighbours didn’t value Sila and Nuna how we did. So, in the midst of humanity’s collective climate crisis, Inuit lives in the arctic are increasingly visually vulnerable.

Reoccurring observations from Inuit elders, hunters and community members show us that our aniuvat (permanent snow patches) are decreasing in size. Sea ice conditions have changed. Temperature has increased. The length and timing of the traditional Inuit seasons have changed. Inuit perspectives on climate change are built on lifetimes of observing the environment. Climate change impacts the way we live, interact and know the world.

Sedna warns “we are on thin ice”.

Exhibition essay by Katherine Takpannie

Opening Reception

September 21, 2024 2:00 pm – 5:00 pmArtist Links

Included Artworks

Nirijunga #1, 2023

Katherine Takpanniearchival pigment ink print, ed. of 5 2AP 24" x 36"/ ed. 3 2AP 36" x 54"

Nirijunga #2, 2023

Katherine Takpanniearchival pigment ink print, ed. of 5 2AP 24" x 36"/ ed. 3 2AP 36" x 54"

Sedna #22, 2023

Katherine Takpanniearchival pigment ink print, ed. of 5 2AP 24" x 36"/ ed. 3 2AP 36" x 54"

Sedna #15, 2023

Katherine Takpanniearchival pigment ink print, ed. of 5 2AP 24" x 36"/ ed. 3 2AP 36" x 54"

Potential to Rise #4, 2023

Katherine Takpanniearchival pigment ink print, ed. of 5 2AP 24" x 36"/ ed. 3 2AP 36" x 54"

'Il faut cultiver notre jardin' #1, 2024

Katherine Takpanniearchival pigment ink print, ed. of 5 2AP 24" x 36"/ ed. 3 2AP 36" x 54"

Chrysalis #1, 2024

Katherine Takpanniearchival pigment ink print, ed. of 5 2AP 24" x 36"/ ed. 3 2AP 36" x 54"

Trickster #1, 2023

Katherine Takpanniearchival pigment ink print, ed. of 5 2AP 24" x 36"/ ed. 3 2AP 36" x 54"

Ookpik | ᐅᒃᐱᒃ #1, 2023

Katherine Takpanniearchival pigment ink print, ed. of 5 2AP 24" x 36"/ ed. 3 2AP 36" x 54"

The Lucifer Effect #1, 2023

Katherine Takpanniearchival pigment ink print, ed. of 5 2AP 24" x 36"/ ed. 3 2AP 36" x 54"

Amorak #1, 2023

Katherine Takpanniearchival pigment ink print, ed. of 5 2AP 24" x 36"/ ed. 3 2AP 36" x 54"

Tulugaq #3, 2023

Katherine Takpanniearchival pigment ink print, ed. of 5 2AP 24" x 36"/ ed. 3 2AP 36" x 54"

Nunavummit #1, 2024

Katherine Takpanniearchival pigment ink print, ed. of 5 2AP 24" x 36"/ ed. 3 2AP 36" x 54"