Ilan Averbuch has created a series of works of wood, lead, steel, glass and stone that dialogue with the gallery’s high ceilings and large open space. The tone of the exhibition is simultaneously monumental in scale and private and intimate in feeling. During the past three years while working on his pieces for Intimate Monuments, Averbuch also worked on several large public commission projects throughout the United States and in Israel. Thus the sculptures featured in this show are infused with monumentality akin to public sculptures. They live between earth and sky and transcend the issue of scale that must live within four walls. Titles like “Self Portrait,” “The Loneliness of Queen Hatshepsut” or “Diary,” suggest intimacy, though some of the works soar to thirteen feet in height.

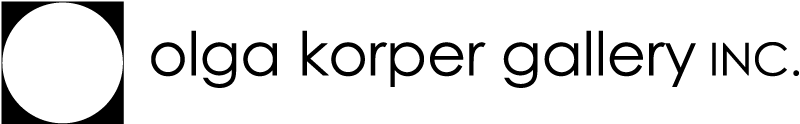

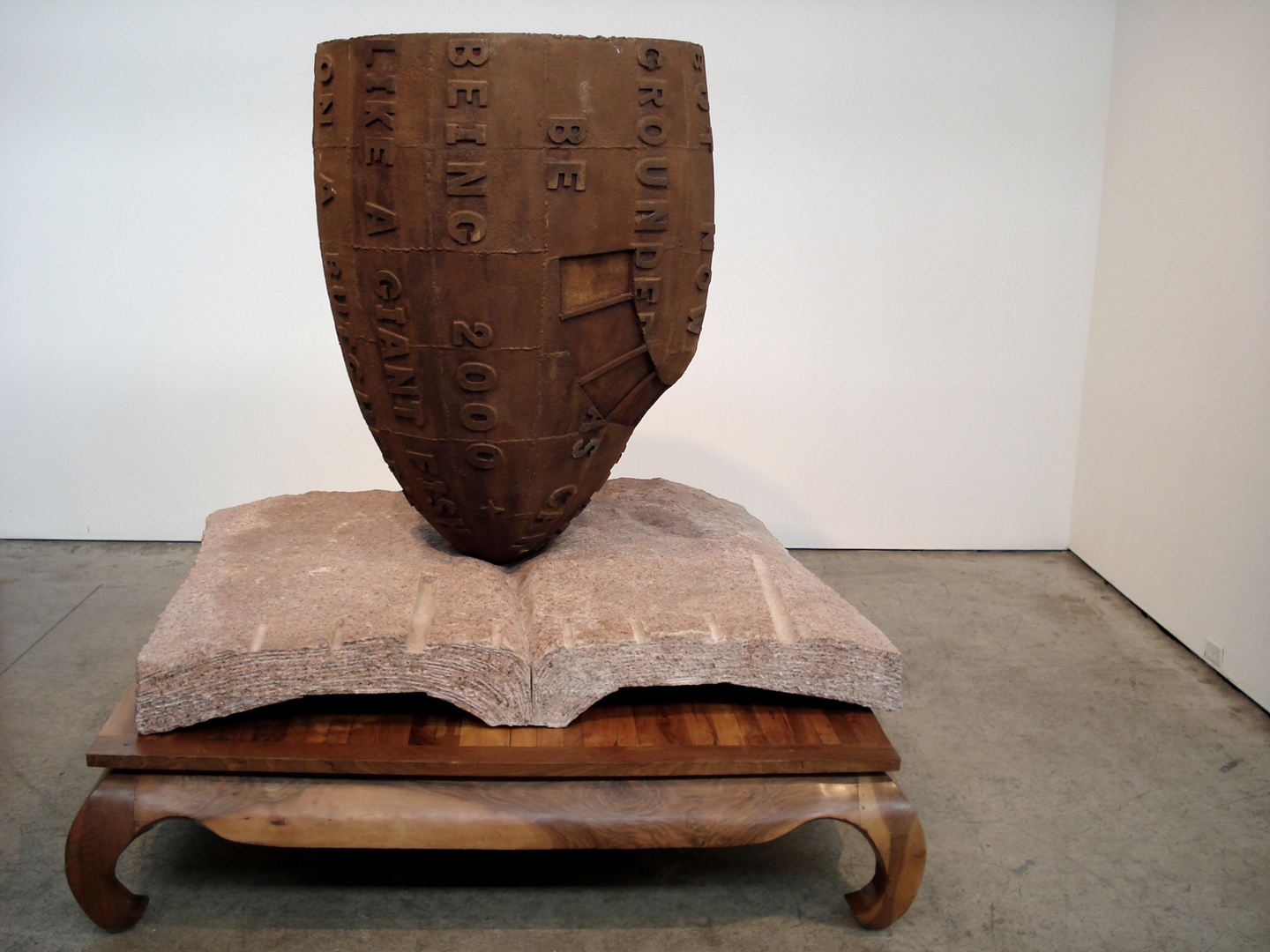

Two of the large works, Being 2000-2008 (in which a steel airplane cockpit balances on a massive stone book) and The Loneliness of Queen Hatshepsut 2008 (in which a large wooden mast holds a massive row of pink granite stones strung on a lead wire), are placed on large living-room-type wooden tables. This creates a modernistic push/pull, an examination of the universal and the private. Tumbleweed is more abstract and economical in material: it is made of stone fragments rising from the floor to a sharp central point, with a massive steel chain piercing the sculpture and tying it to the gallery wall.

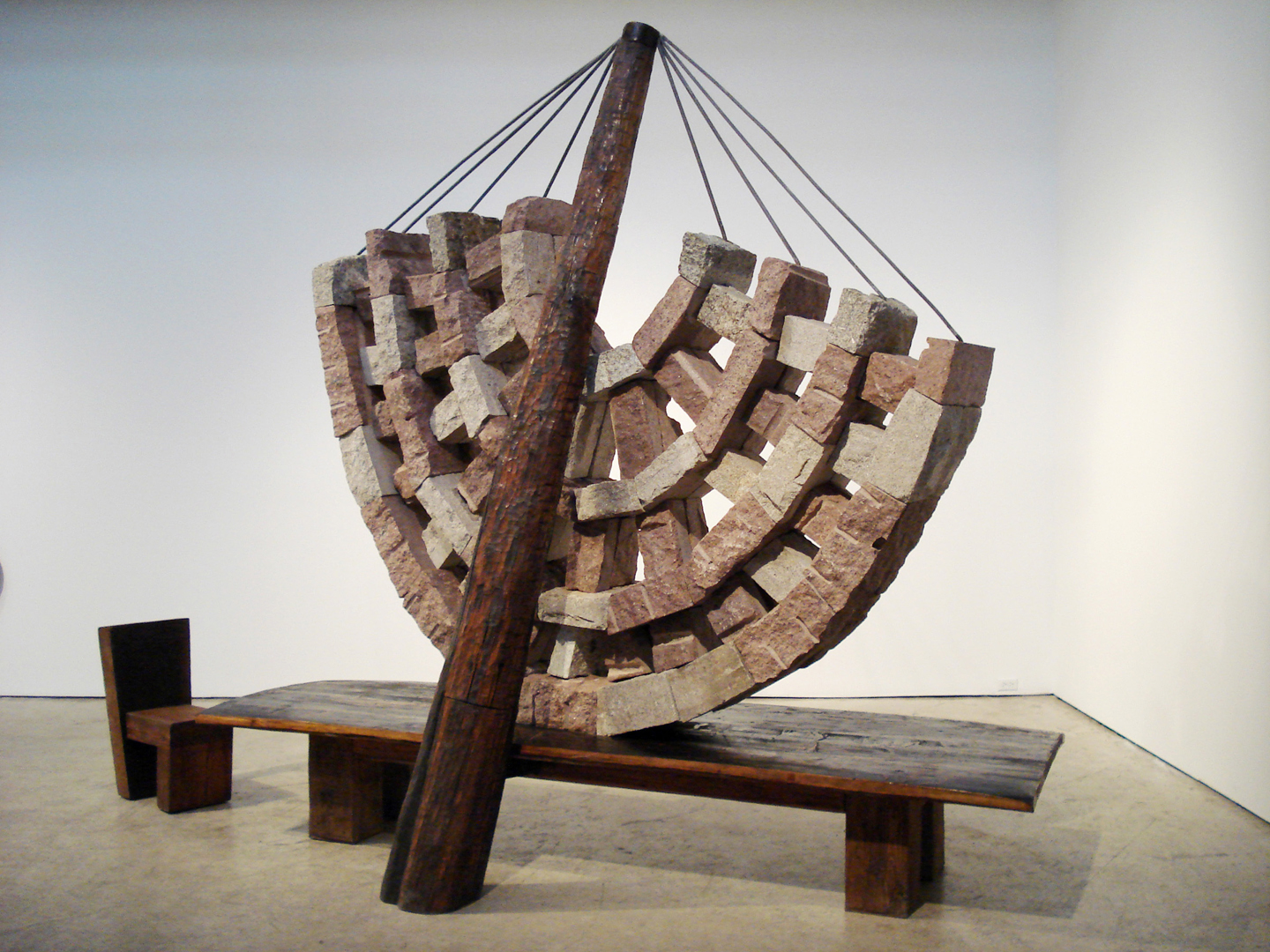

The climax of this array of meditative quests is in Self Portrait, a heroic lead picture frame 13 x 15 x 1.5 feet, standing freely on the gallery floor. It is somewhat tilted, framing a large tree made of steel and semi-opaque glass. The frame and the metaphoric tree are connected and penetrating each other. In Hebrew (the language of Averbuch’s childhood), “Ilan” means “tree.” The same topic occupies another work, Diary (2008), in which a drawing of a blackened tree sprawls through eight massive wood frames with heavy glass. Fragments of writings as background create the landscape in which the tree exists. 10 x 13 feet.

“I build sculptures that try to transform a place or space into an imaginary world. A narrative cycle takes place when one breaks the delicate balance of scale, material, and mass. I often use monumentality as my vehicle,” Averbuch says. “It is to a great extent an assertion of our defiance of the passage of time, of our rejection of the power that belittles us and our ambitions. Yet my work continues to reflect upon the impossibility of the monumental vision. In the end, the search is more about personal identity – reckoning with fundamental existential questions.”

Opening Reception

January 24, 2009 2:00 pm – 5:00 pmArtist Links

Included Artworks

artwork detail