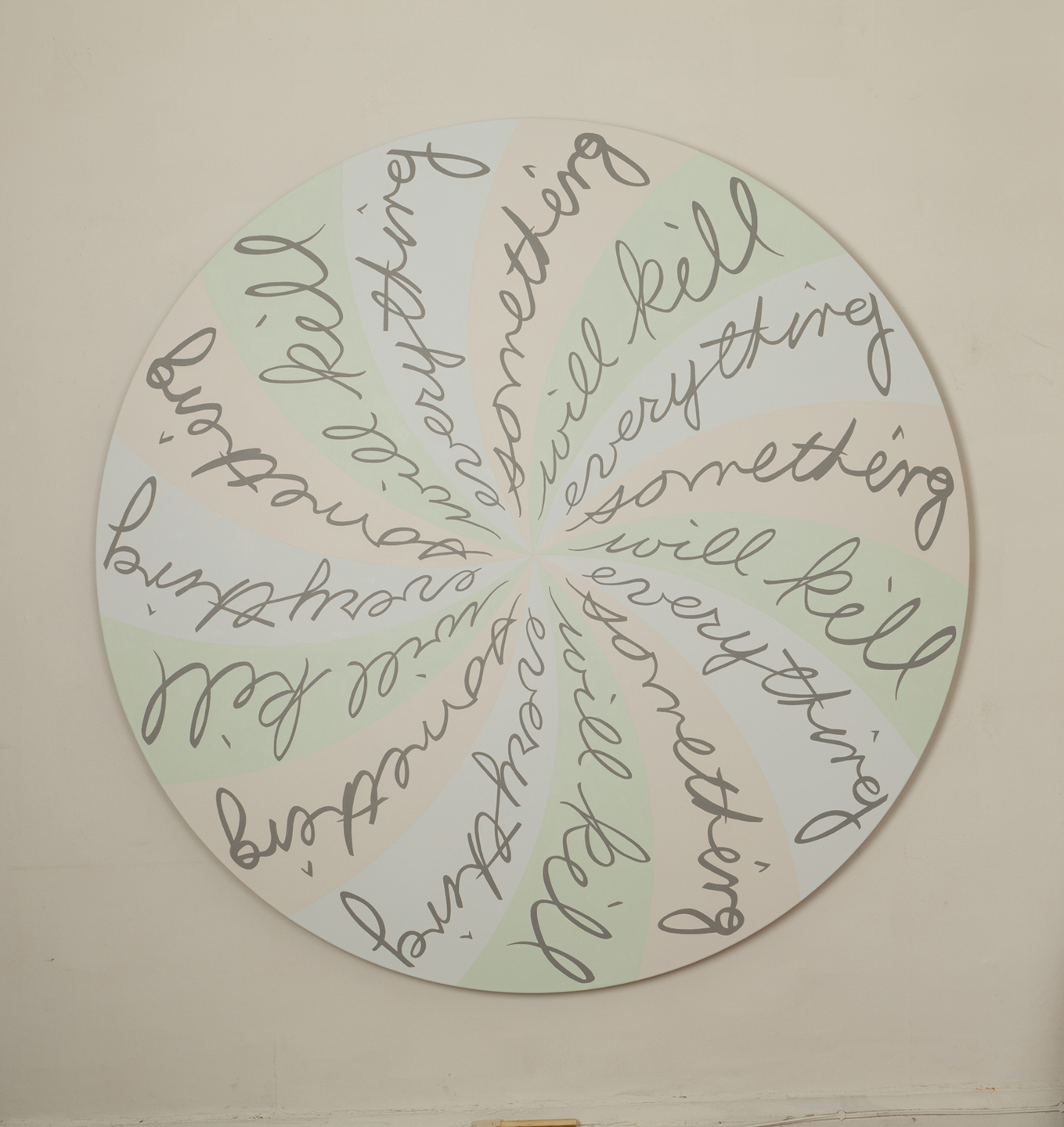

Robert Fones has a close friendship with the written word. Throughout his decades-long career he has featured various fonts and hand-drawn letterforms in his art. Fones’ new works consist of four independent and yet interconnected series – Polar Explorers, Apoptosis, from Aeropagitica and Engines of Life – take a look at text on multiple levels: as a gateway to the past, as abstracted structural forms, as a commentary on social structures and the intertwining natures of reality and fantasy.

The Polar Explorers series was inspired by the discovery of a grade 5 social studies notebook that had belonged to Fones when he was 10 years old. The pages contained notes taken in careful cursive on a handful of famous polar explorers: Scott, Shackleton, Peary, Amundsen, and Byrd. Now an adult, Fones was captivated by the handwriting, reminded of the struggle of learning and practicing cursive script, painstakingly connecting letter to letter. Although his young handwriting was somewhat alien – just on the cusp of being formed and defined – Fones noted how there were distinctive letters and swirls that were still very much part of his scriptive vocabulary today, like a ghostly portrait of an ancestor with exactly your ears, an echo from the past.

“Like seeing a photograph of yourself as a child, encountering handwriting that you know was once yours but that now seems only dimly familiar can inspire a confrontation with the mystery of time.” – Francine Prose

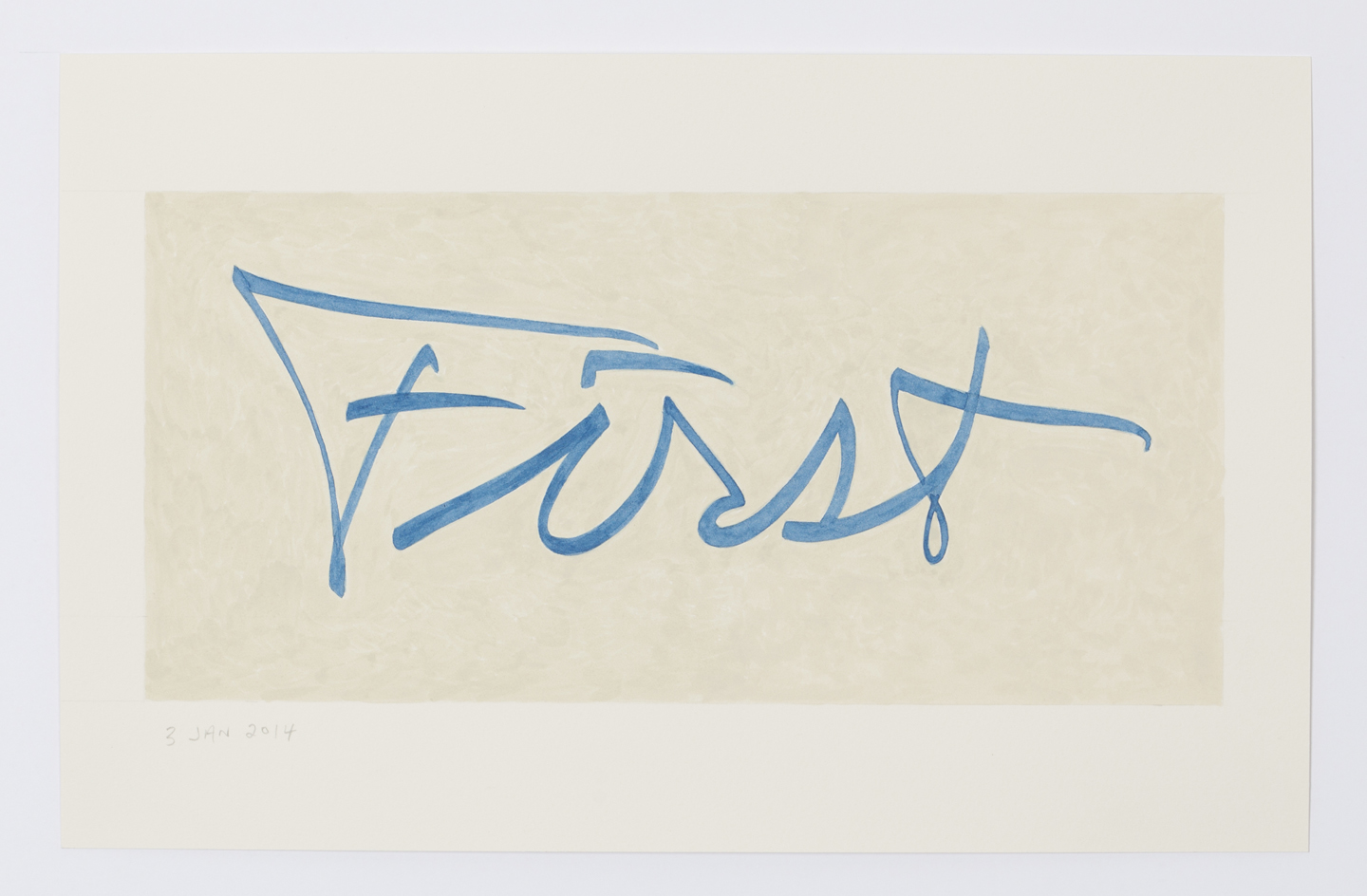

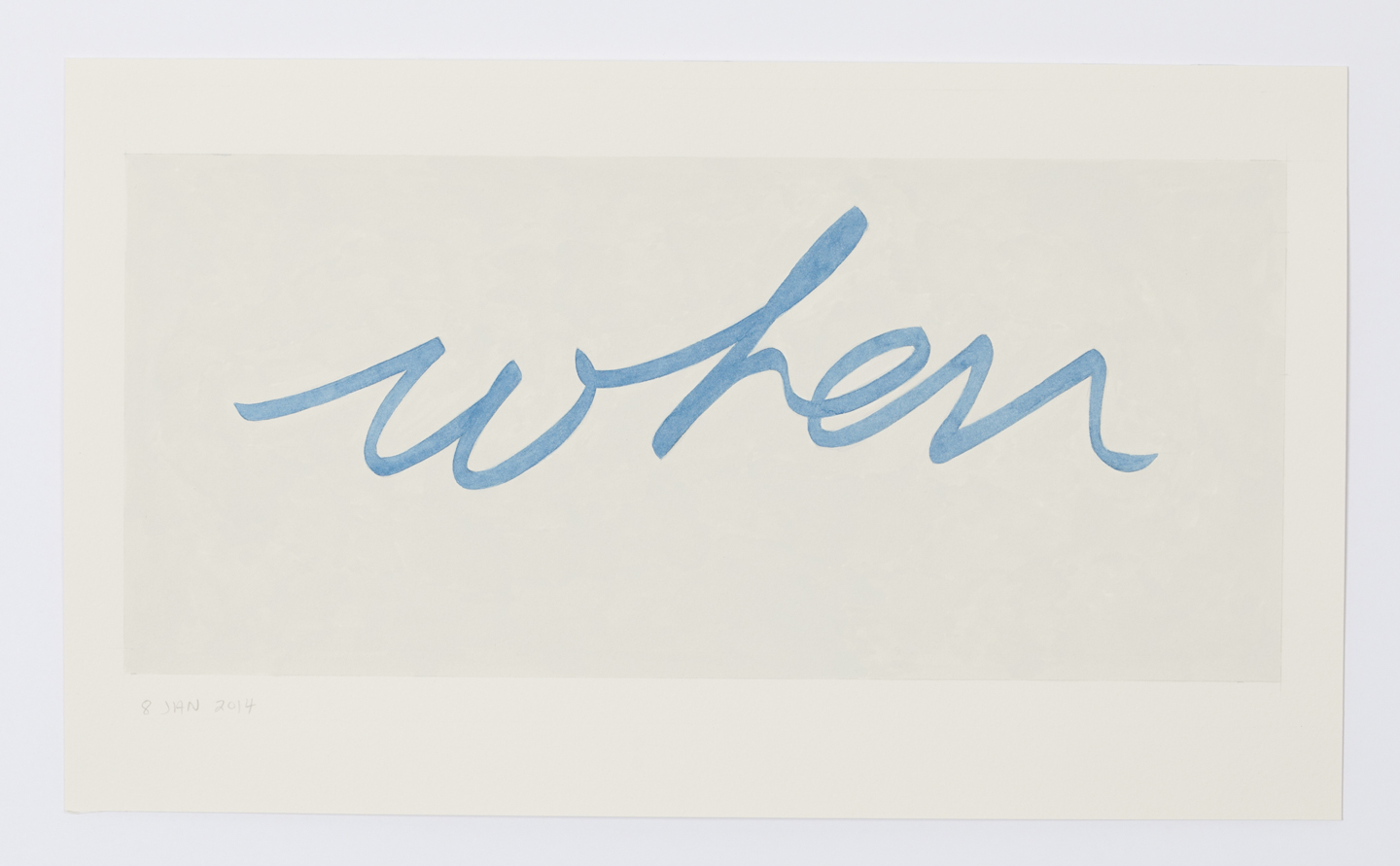

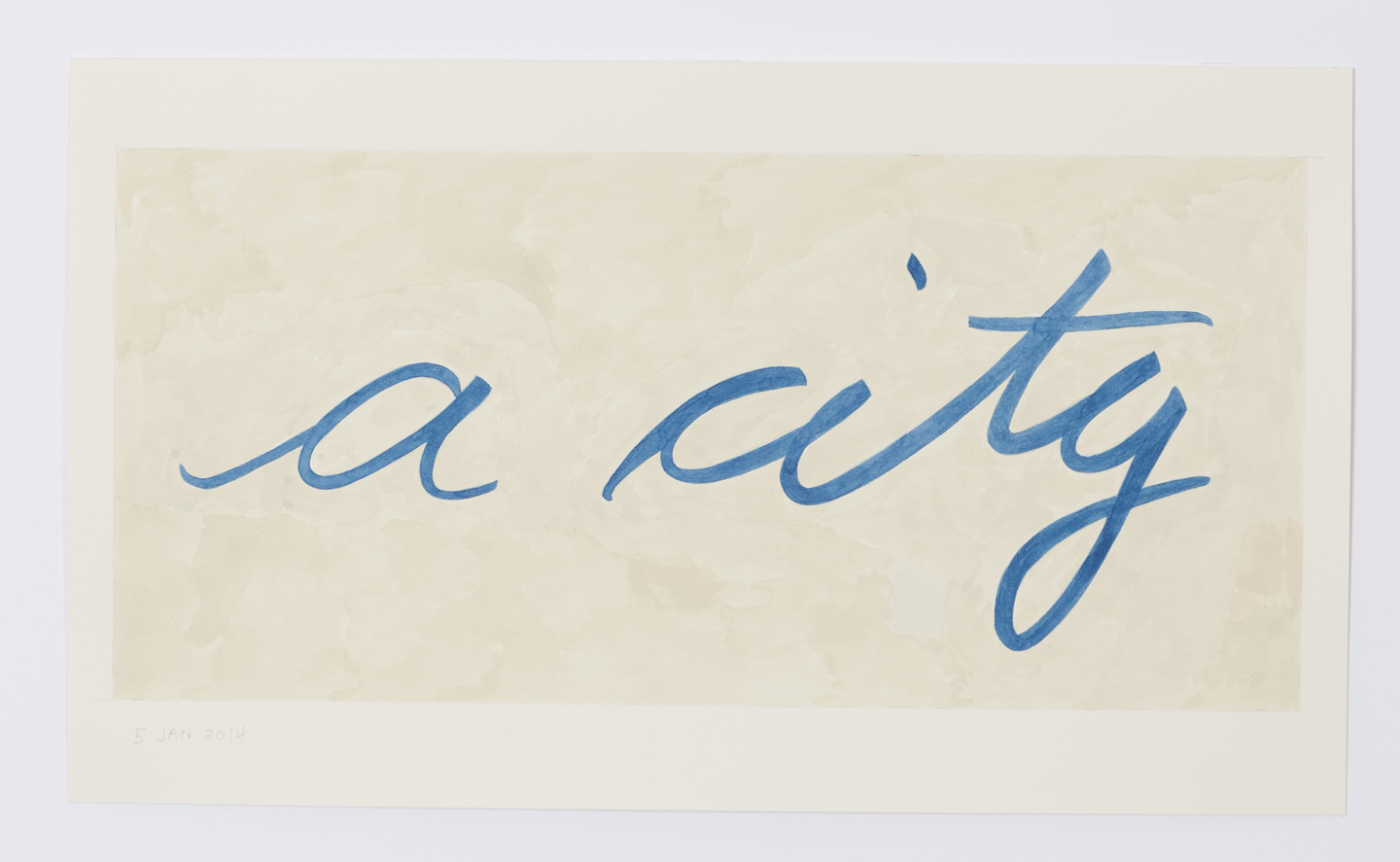

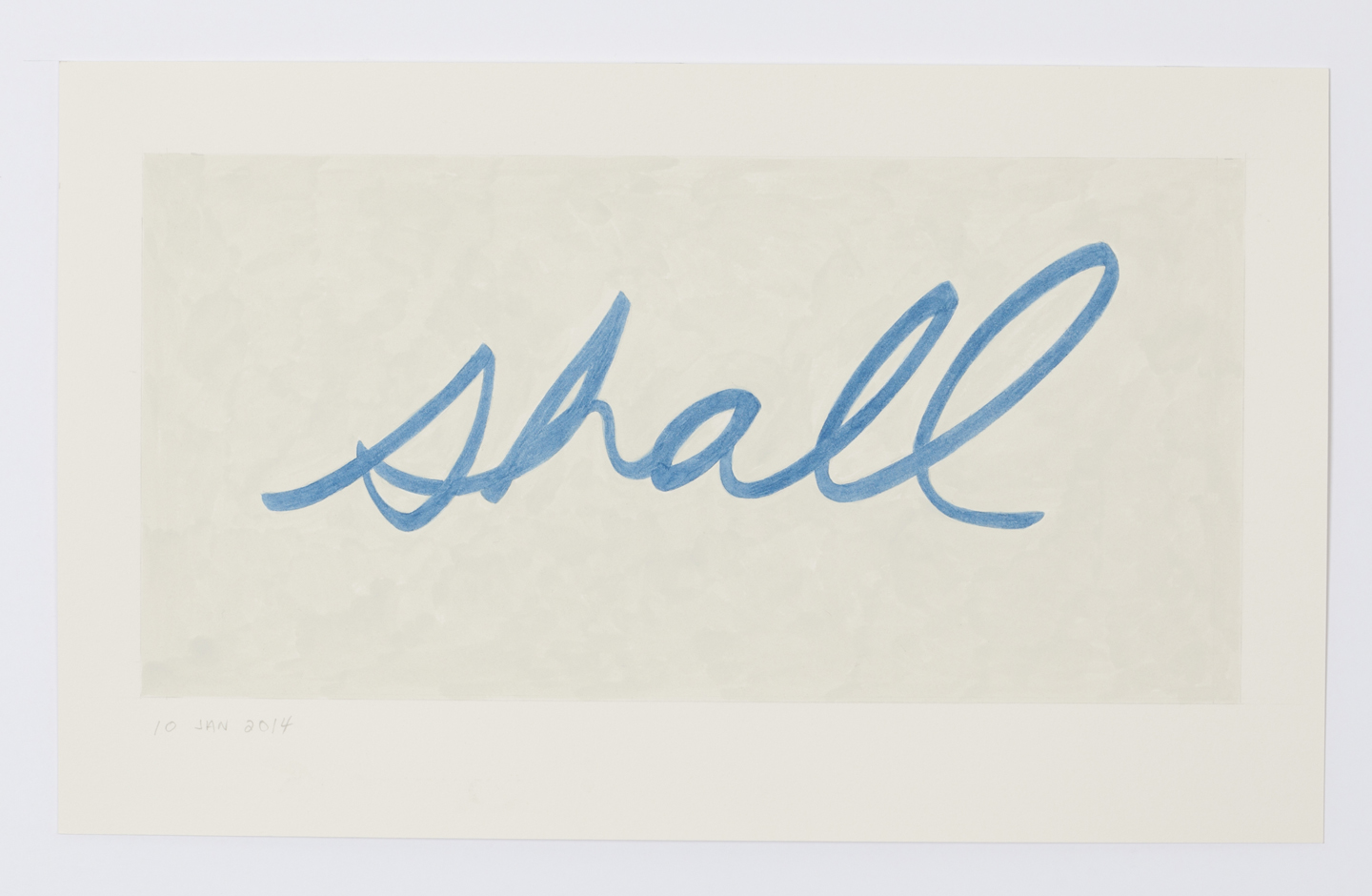

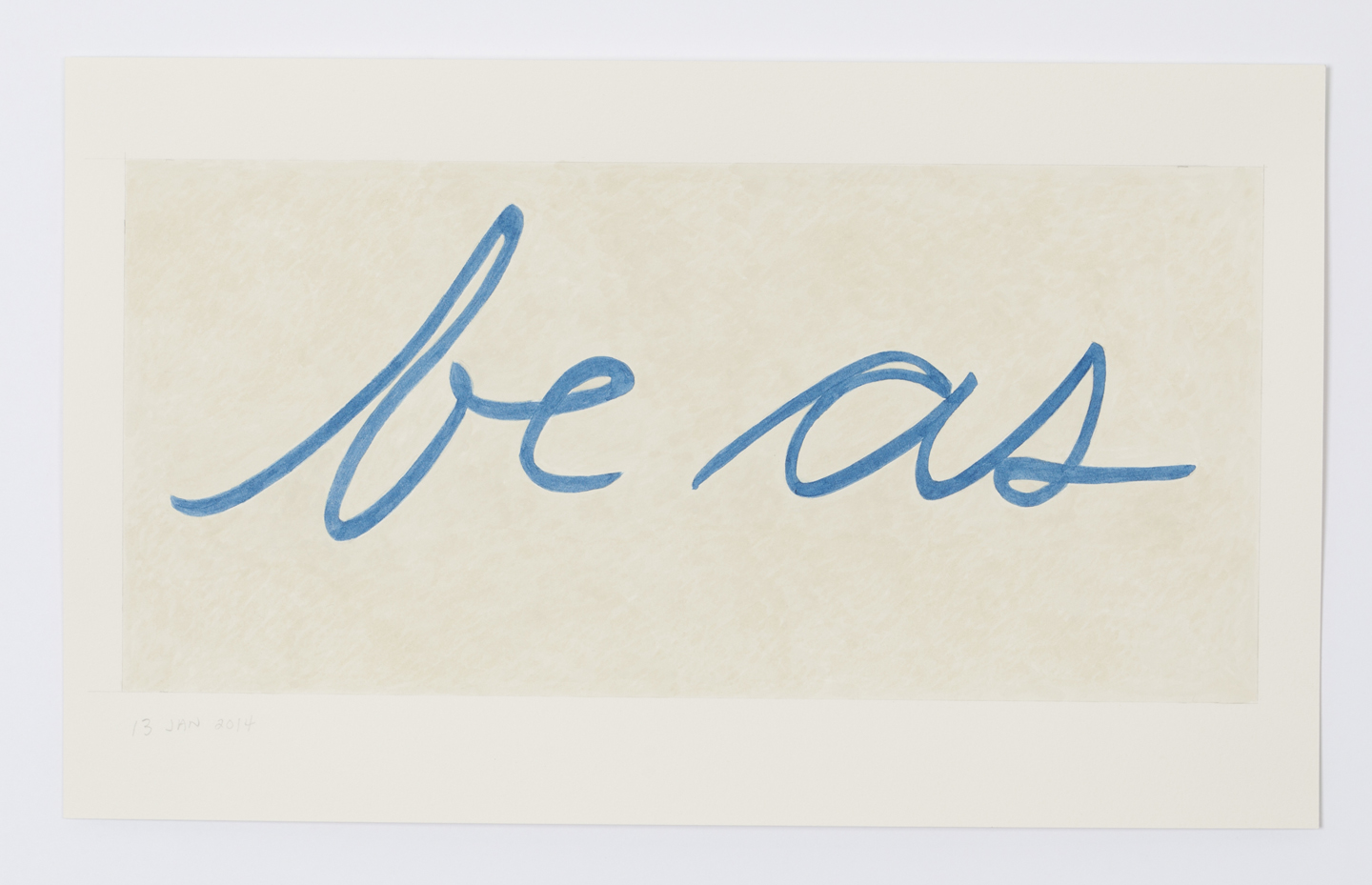

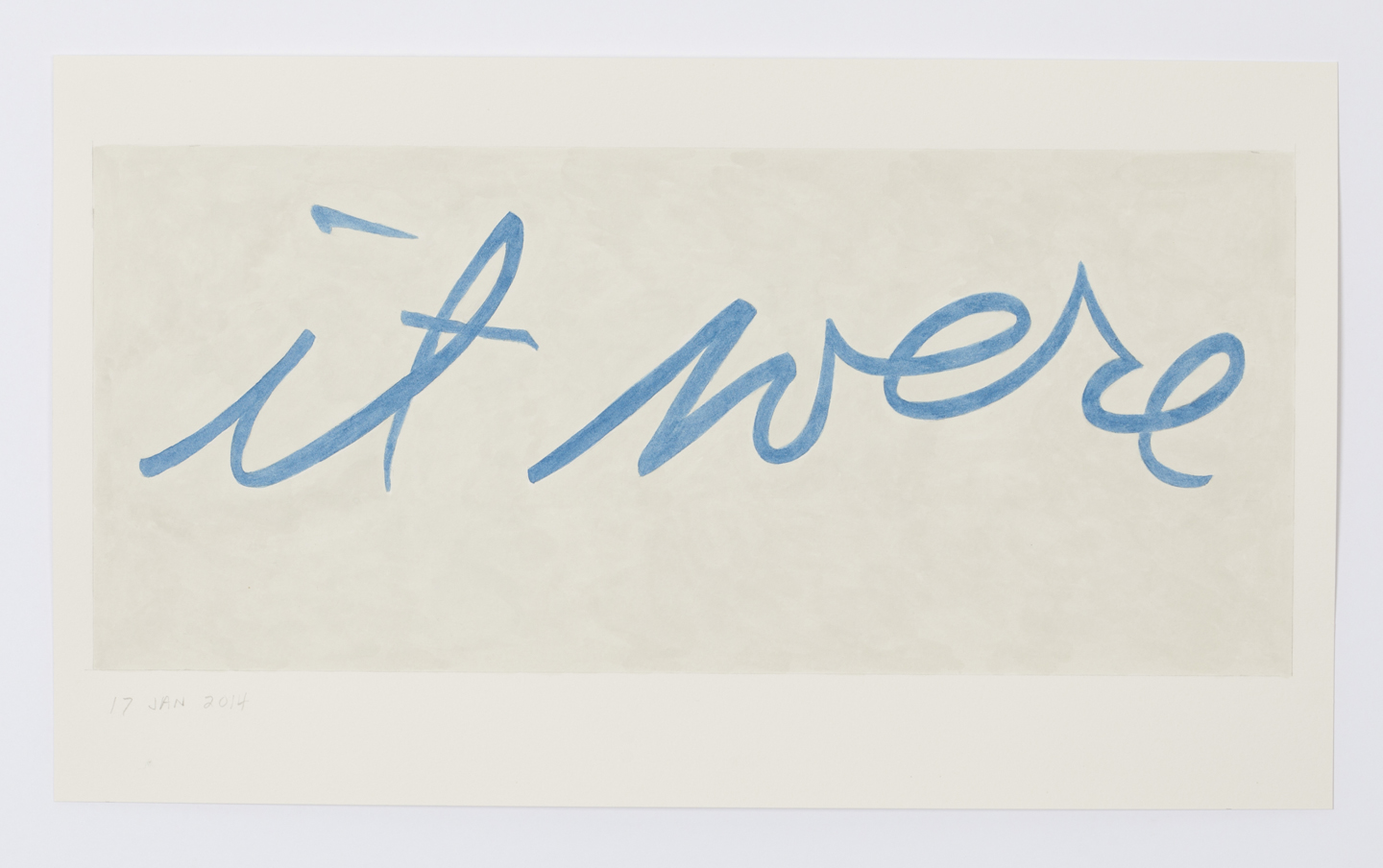

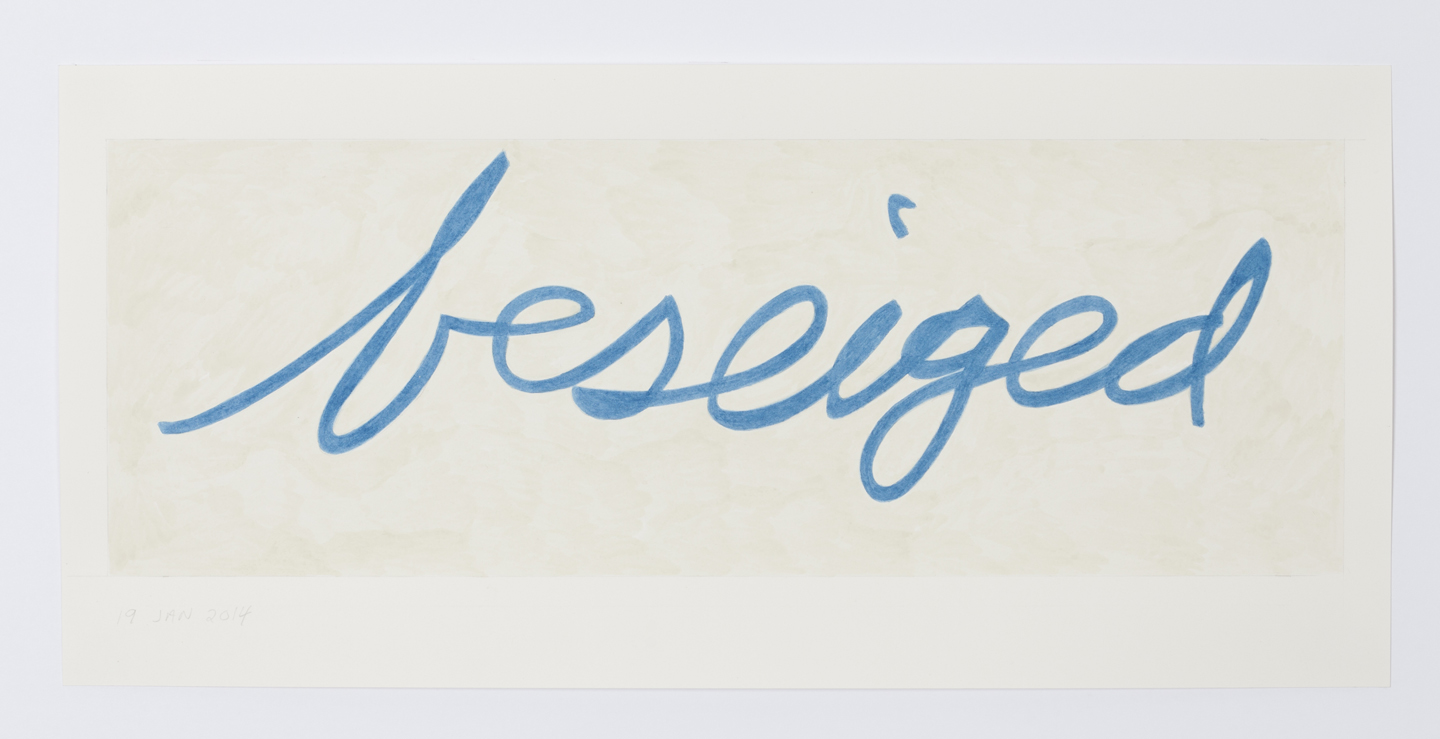

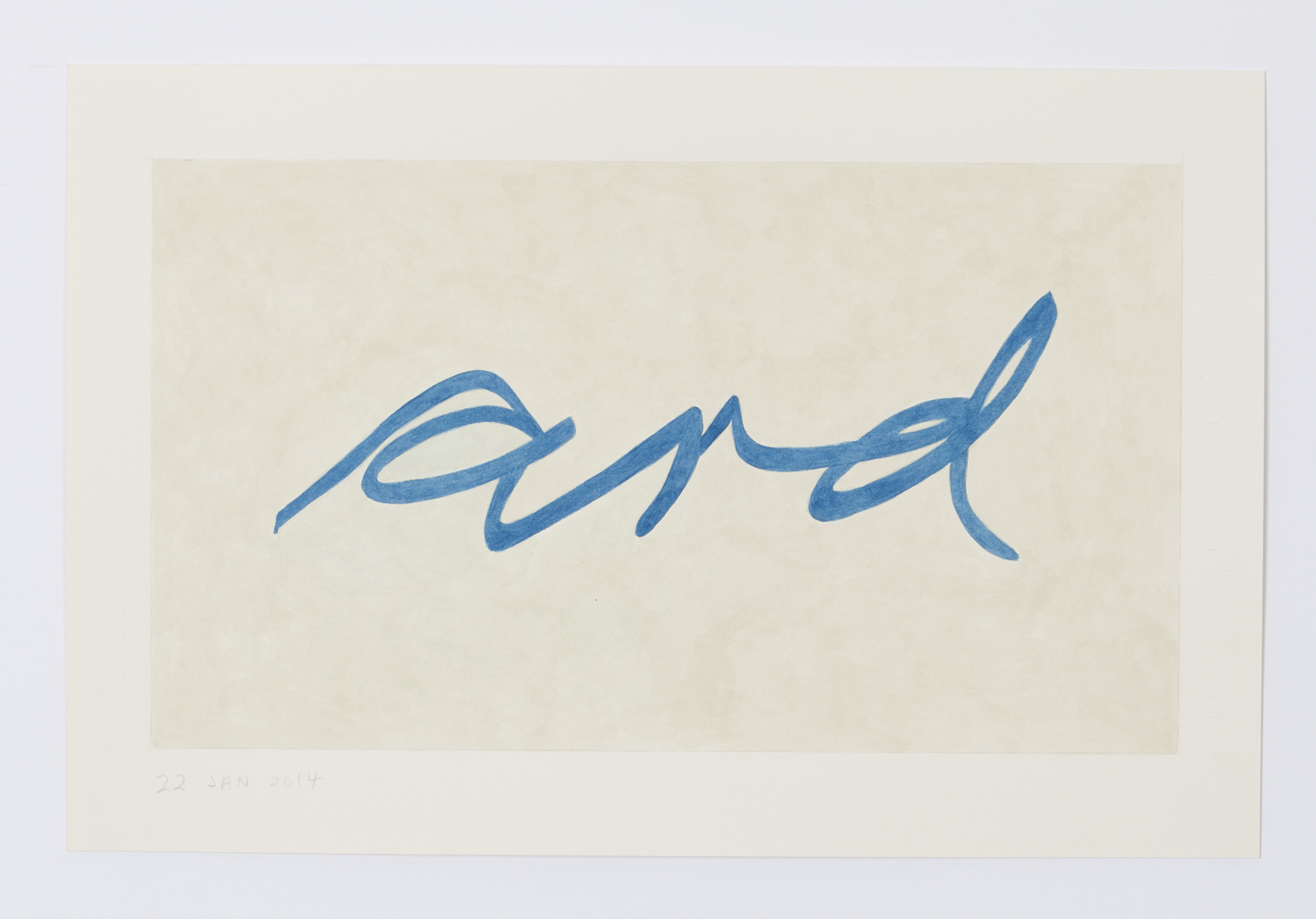

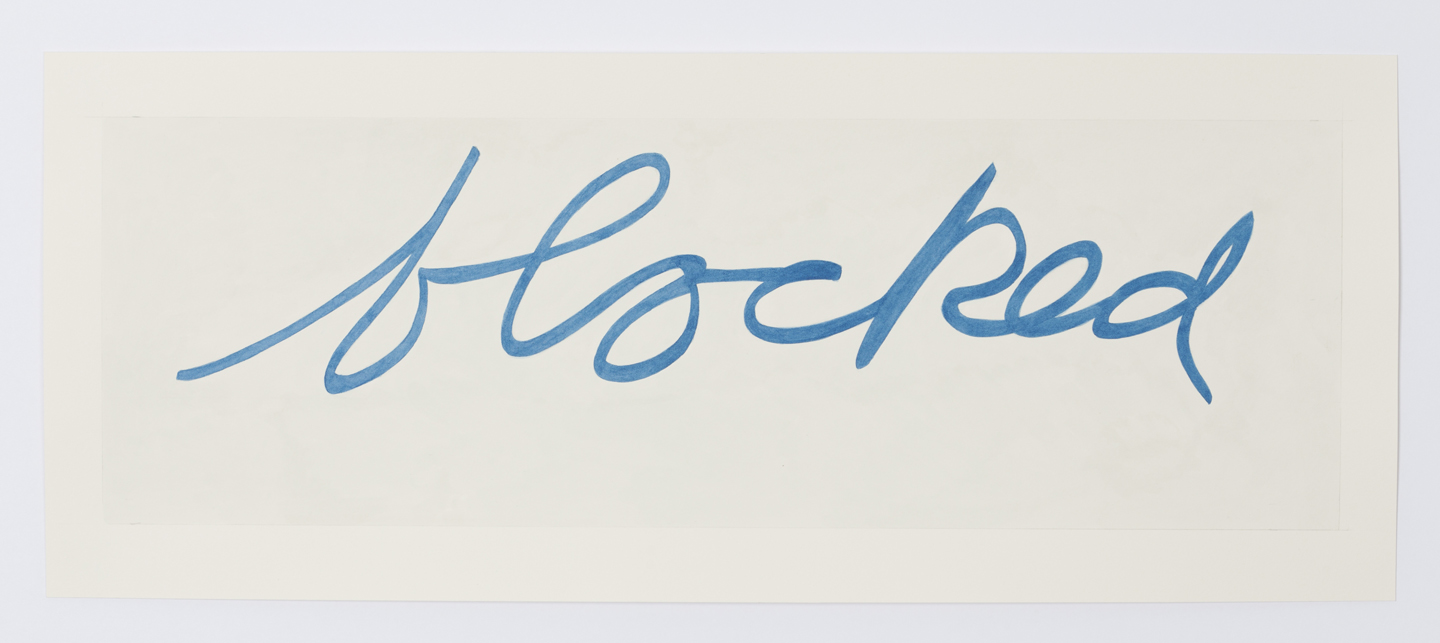

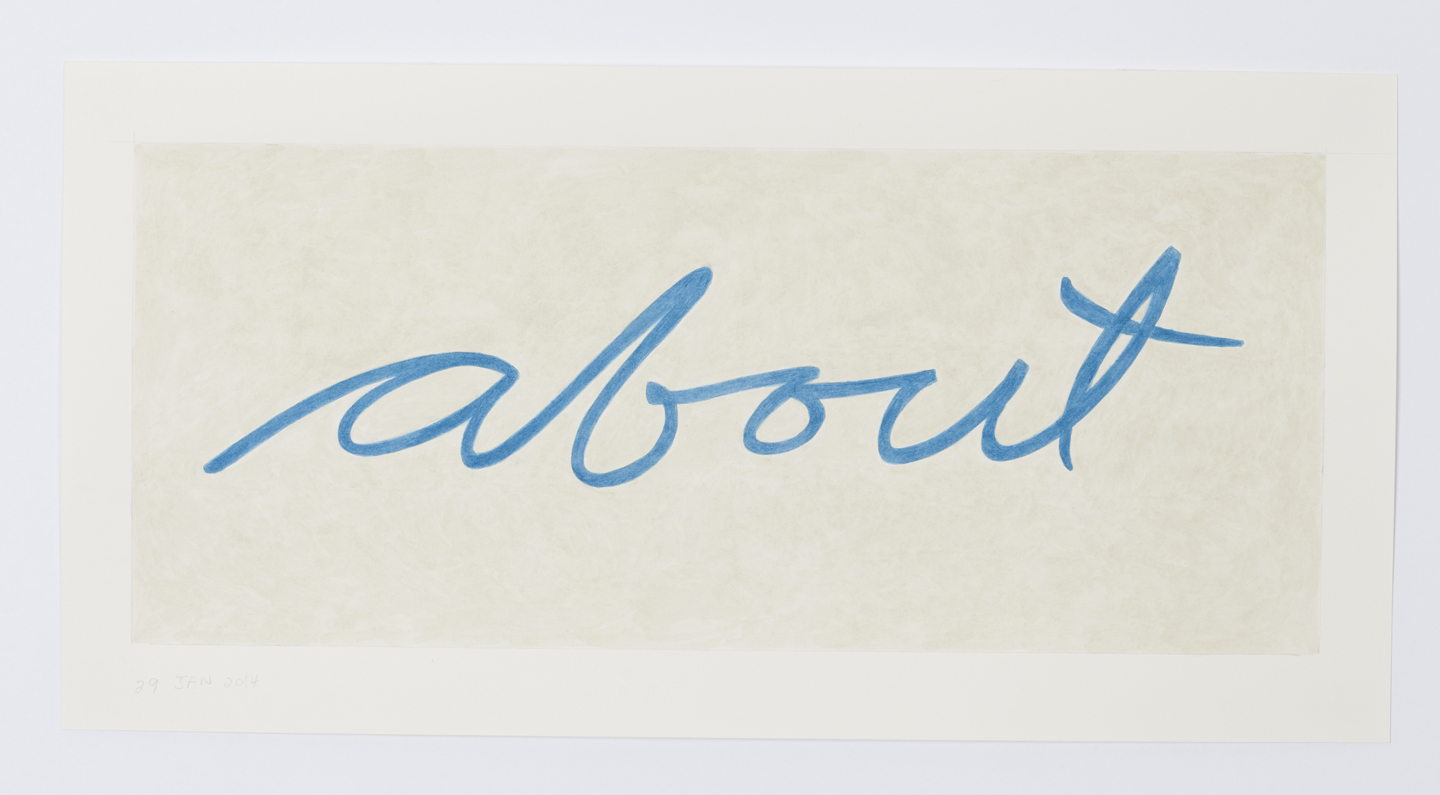

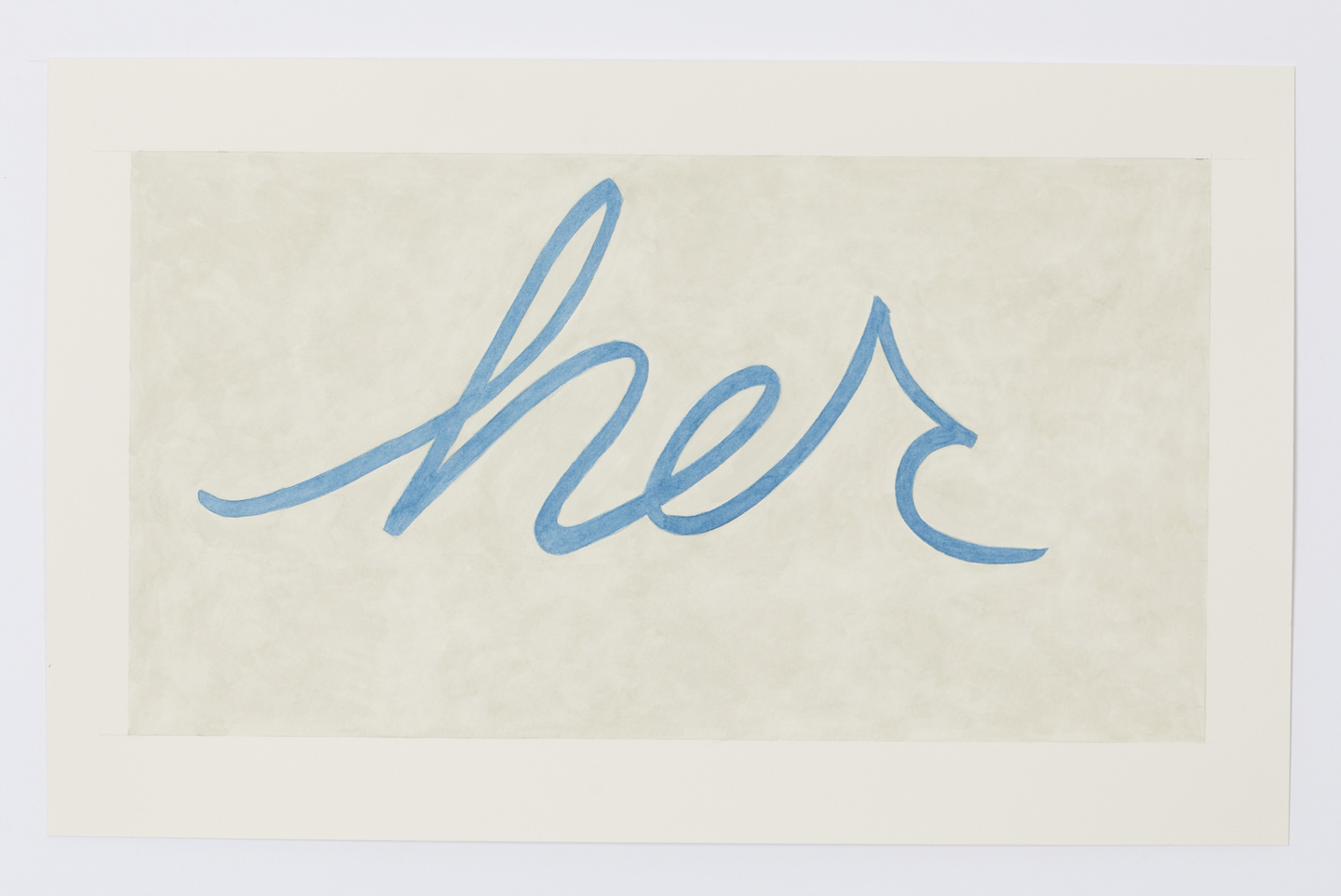

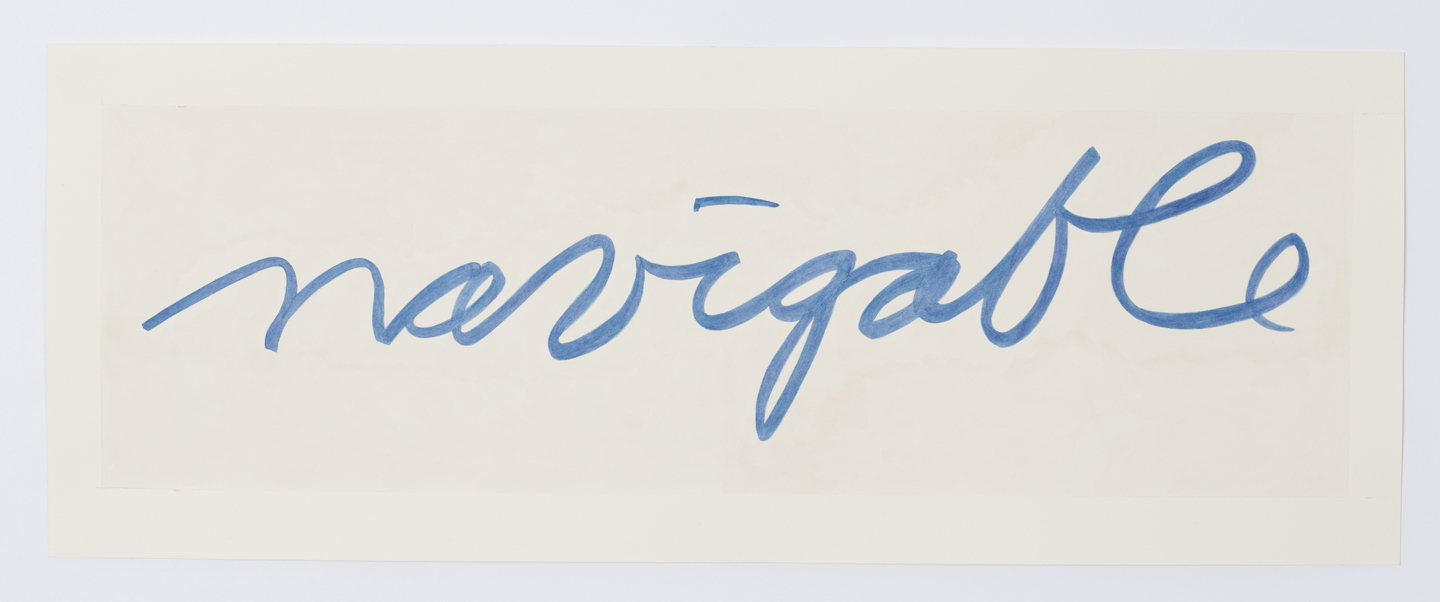

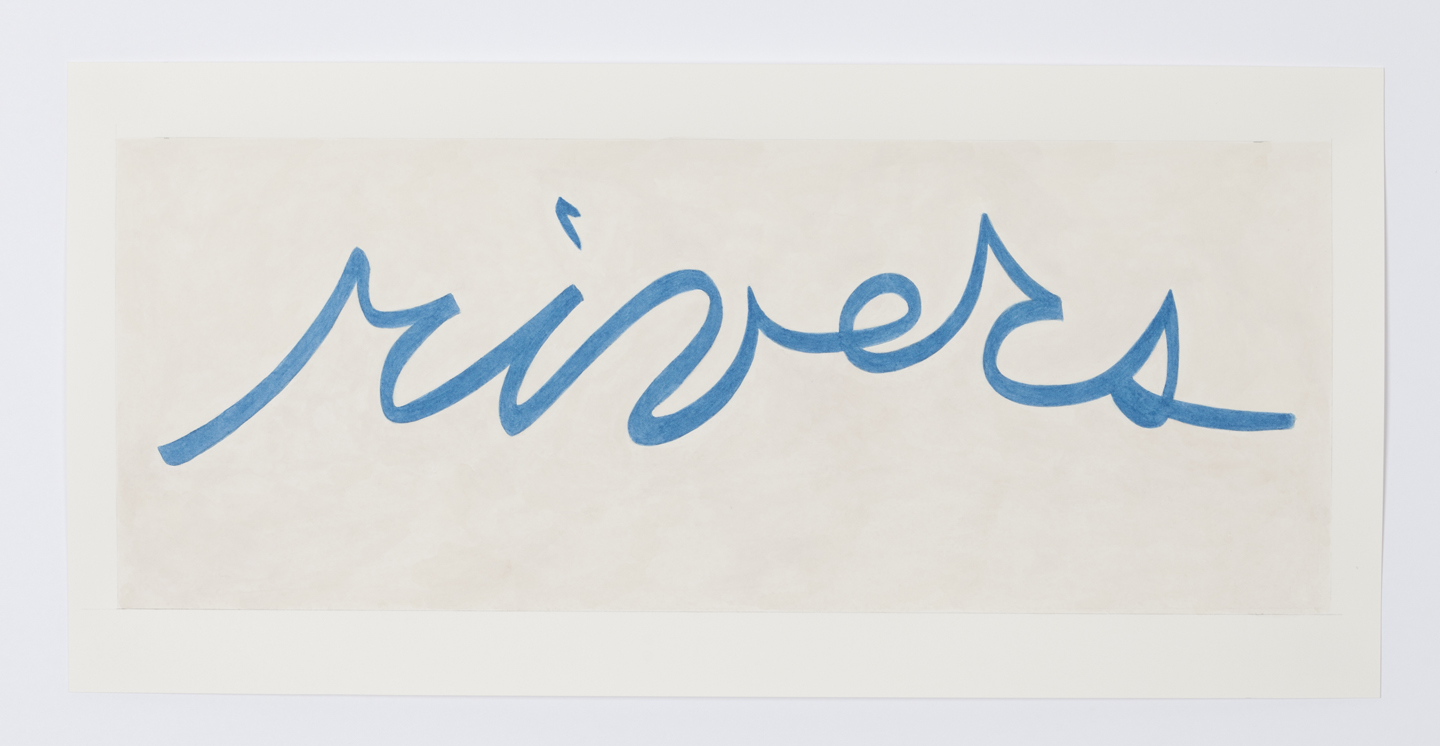

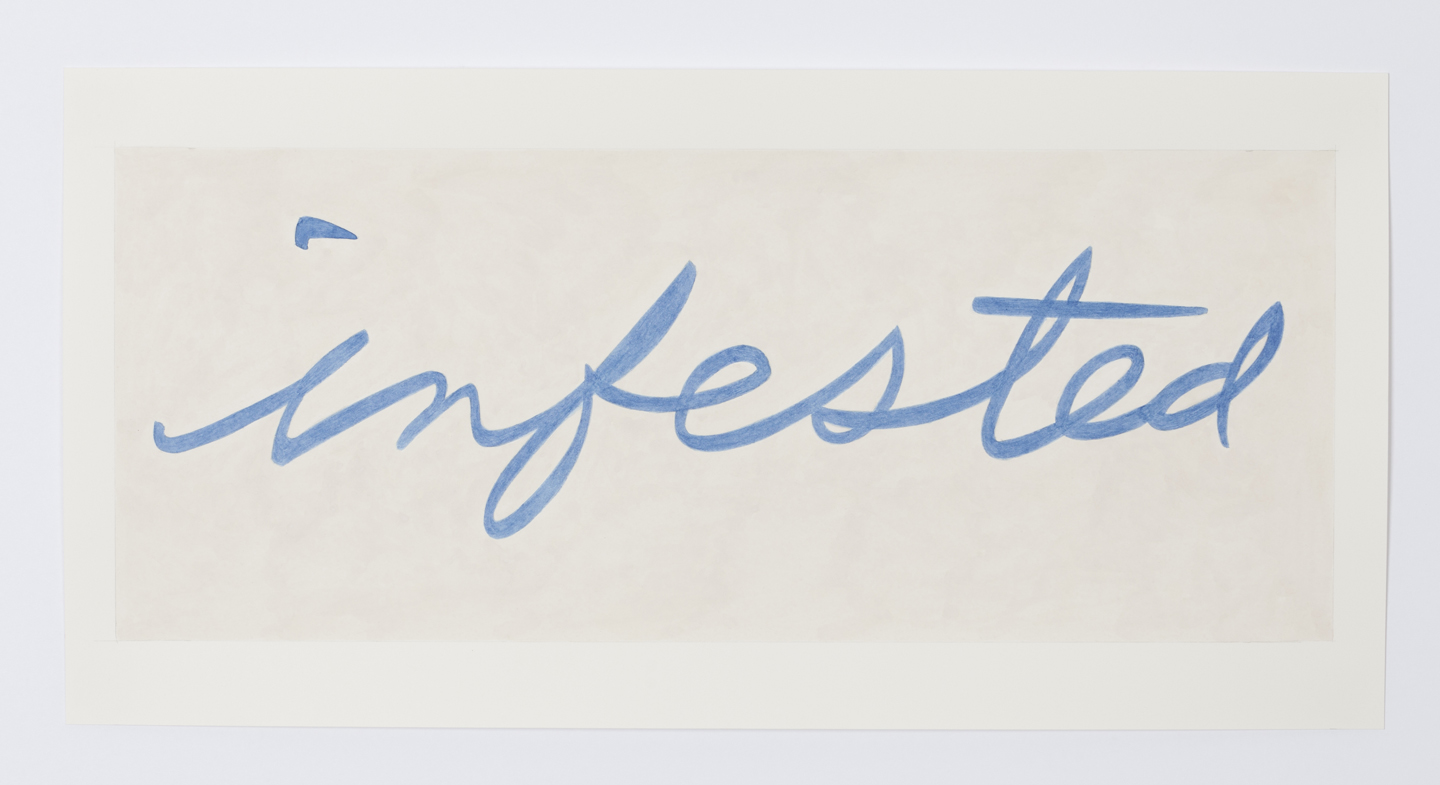

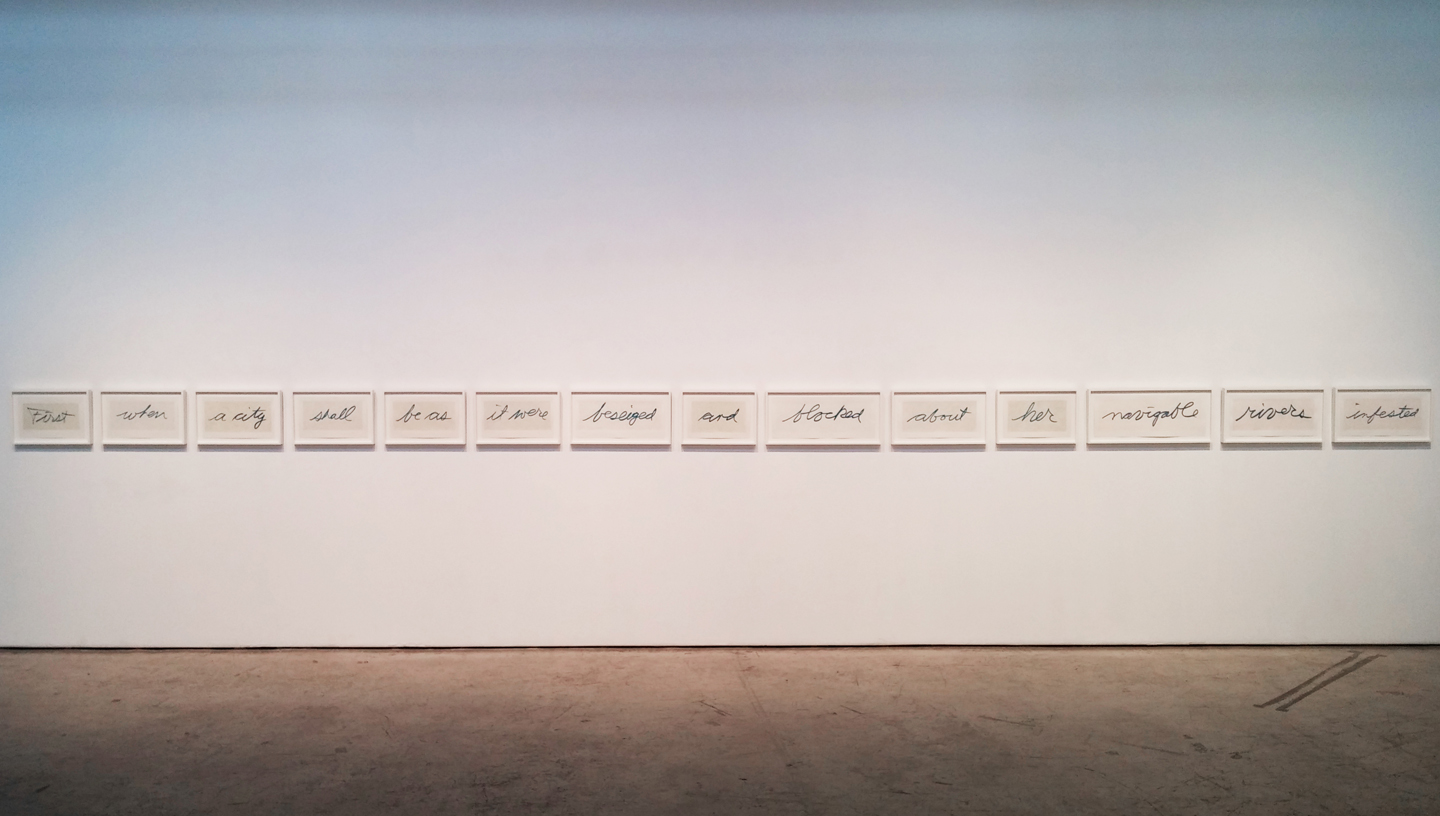

And so, inspired by his elementary hand, Fones made a study of the notebook, seeking to recreate his childhood script on a large scale. He selected fragments of phrases from each of the paragraphs on the Polar Explorers – Scott hoped, Shackleton died, Peary found, Amundsen was, Byrd flew – and wrote the words over and over until he could accurately imitate the ascenders and descenders of his 10-year-old penmanship.

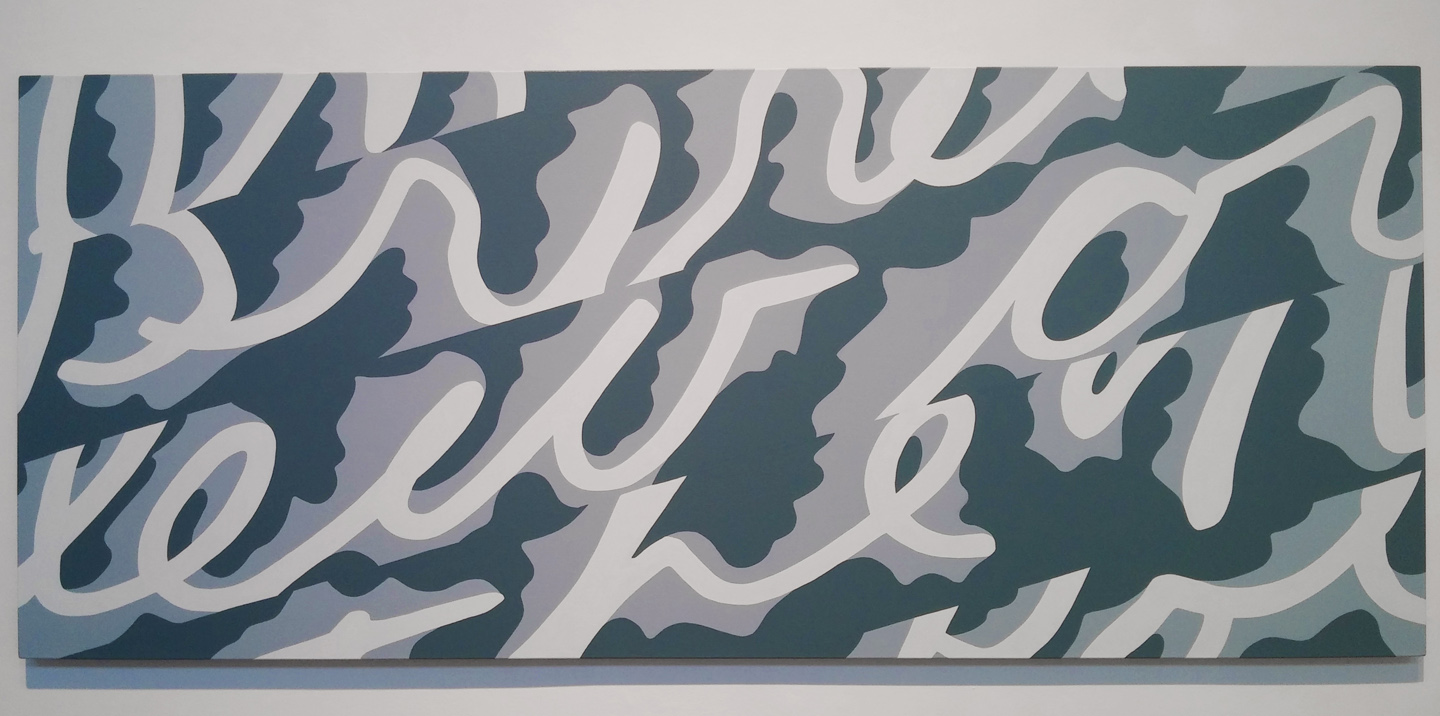

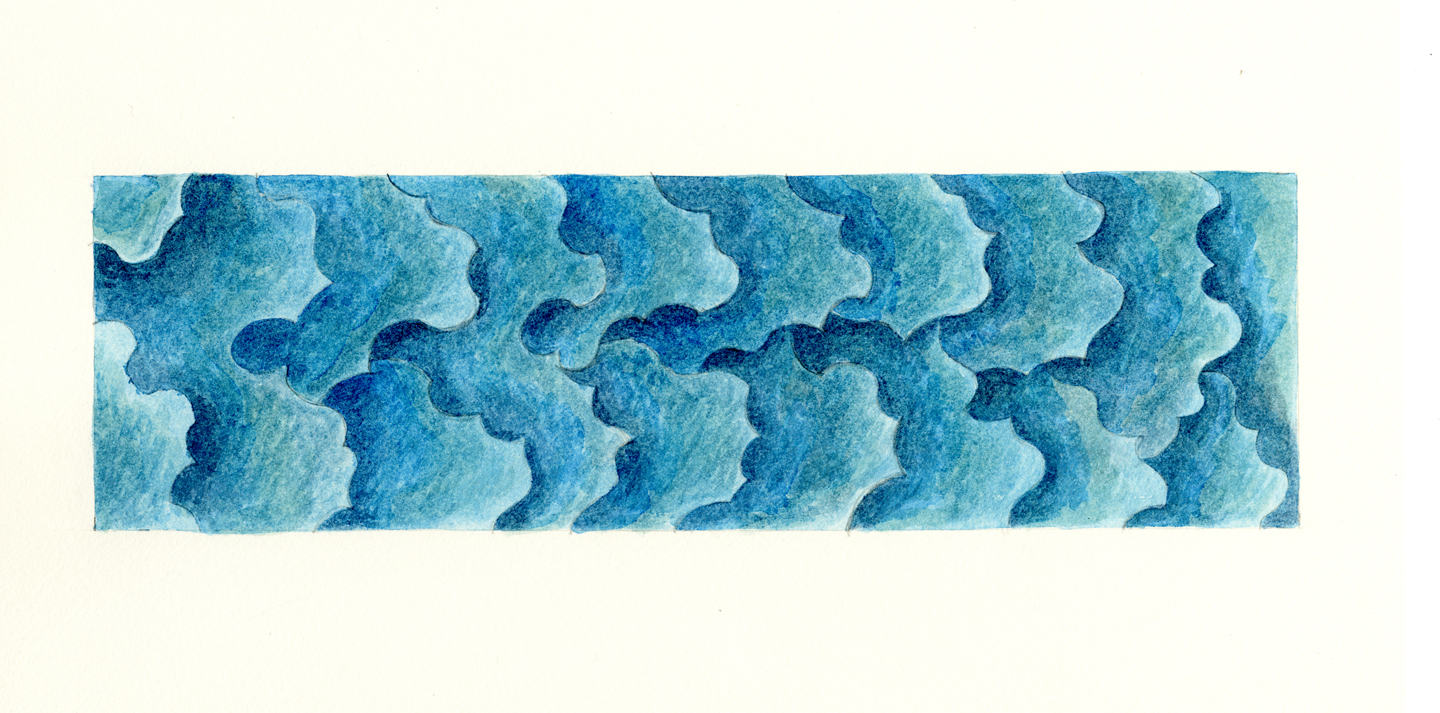

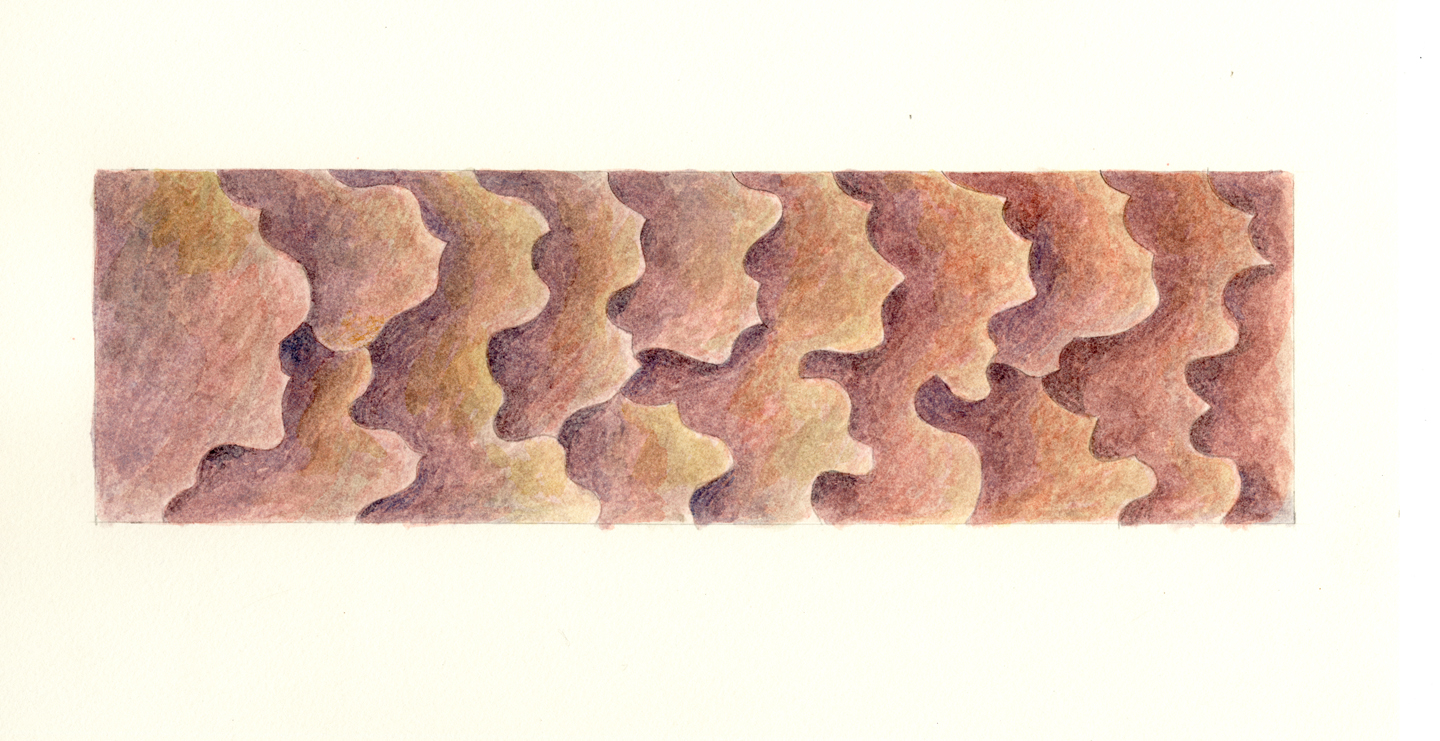

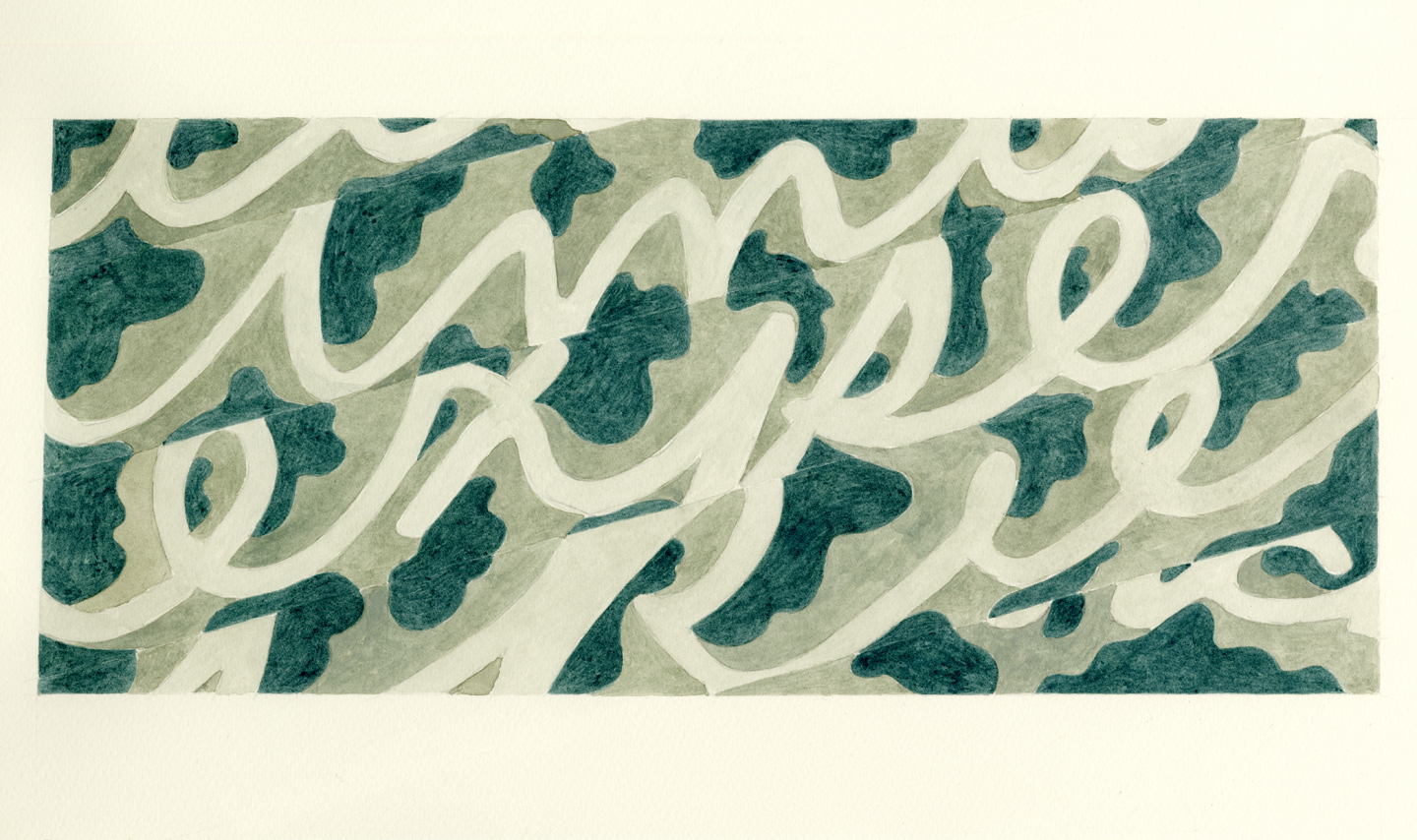

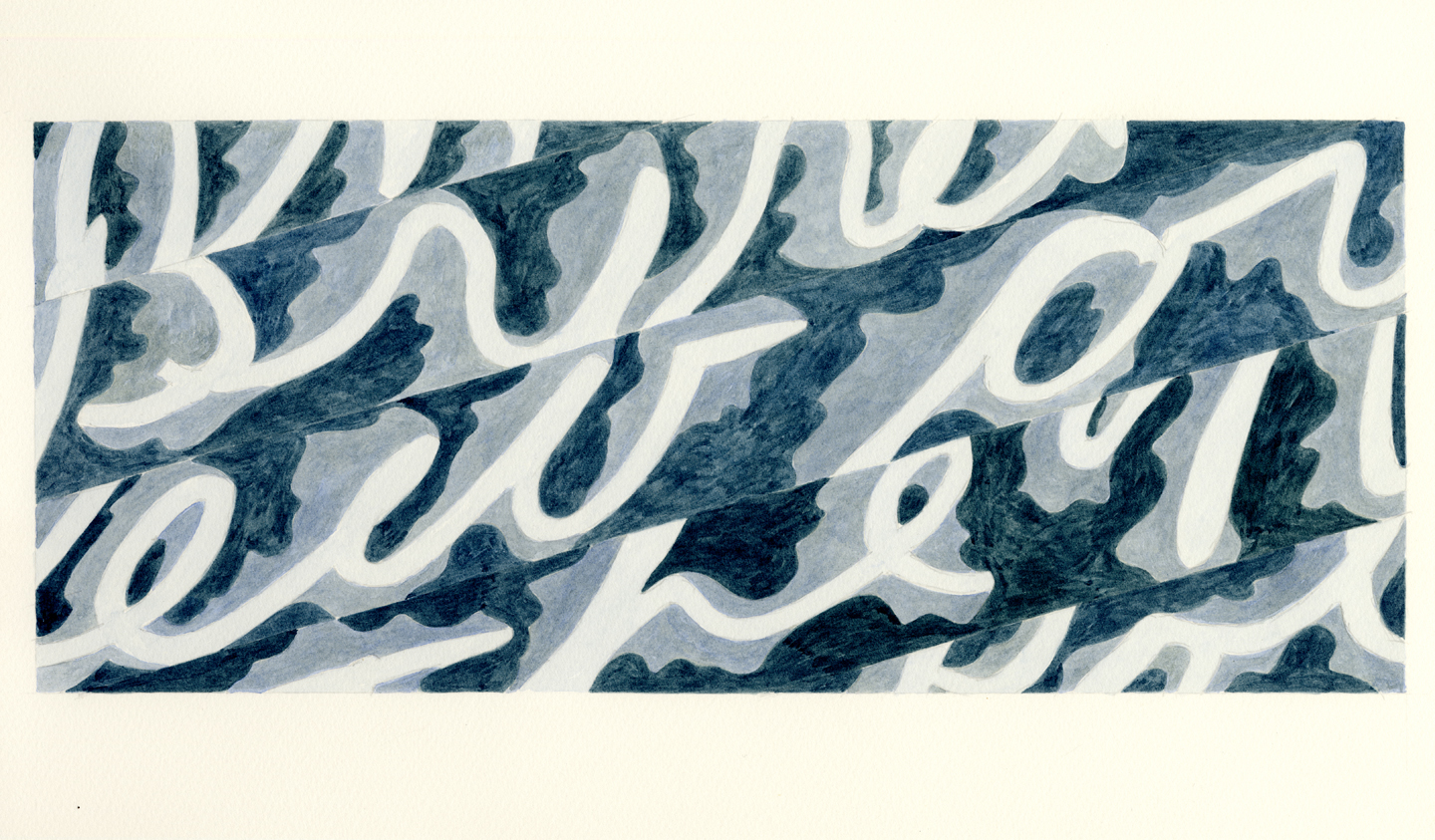

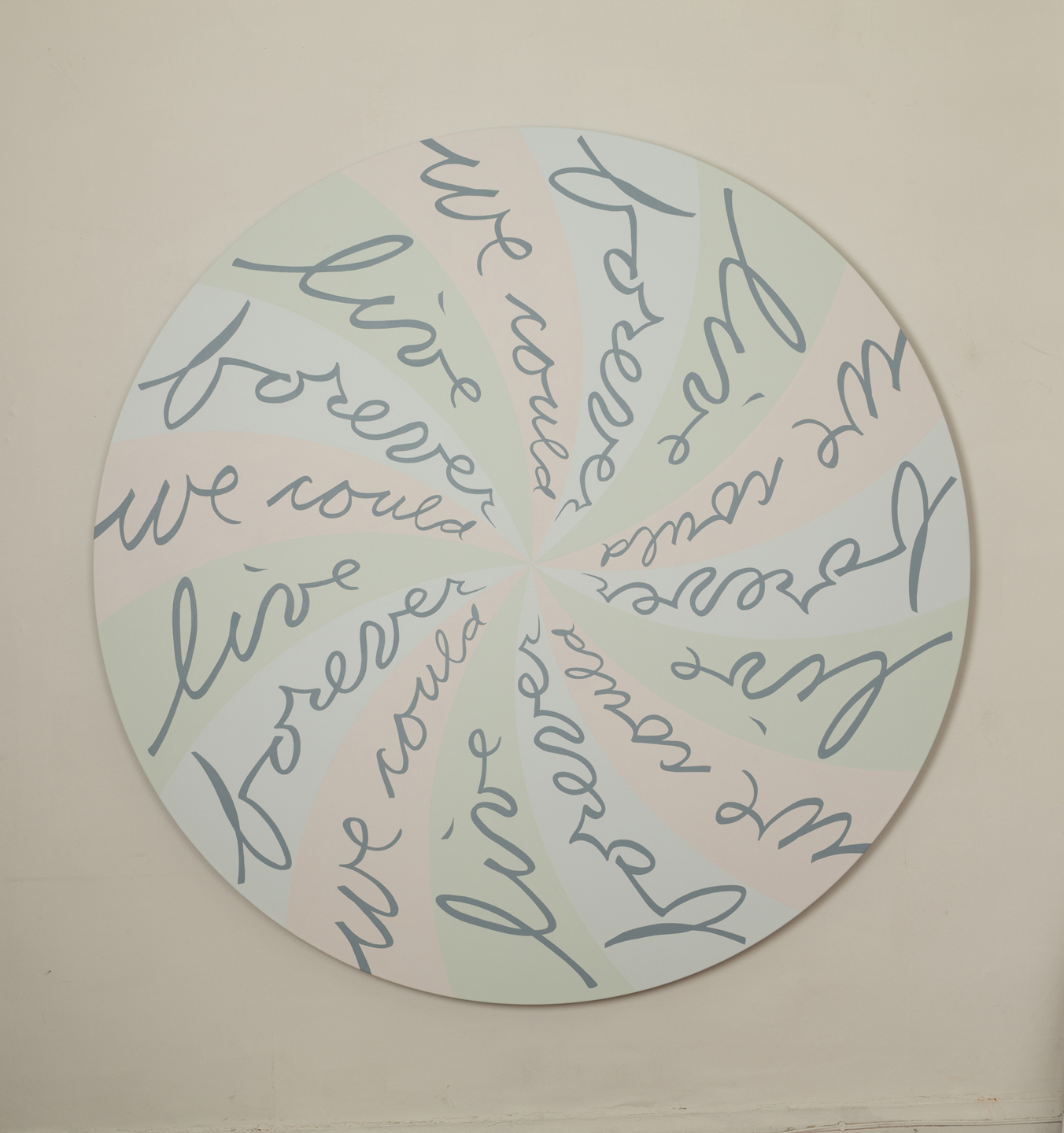

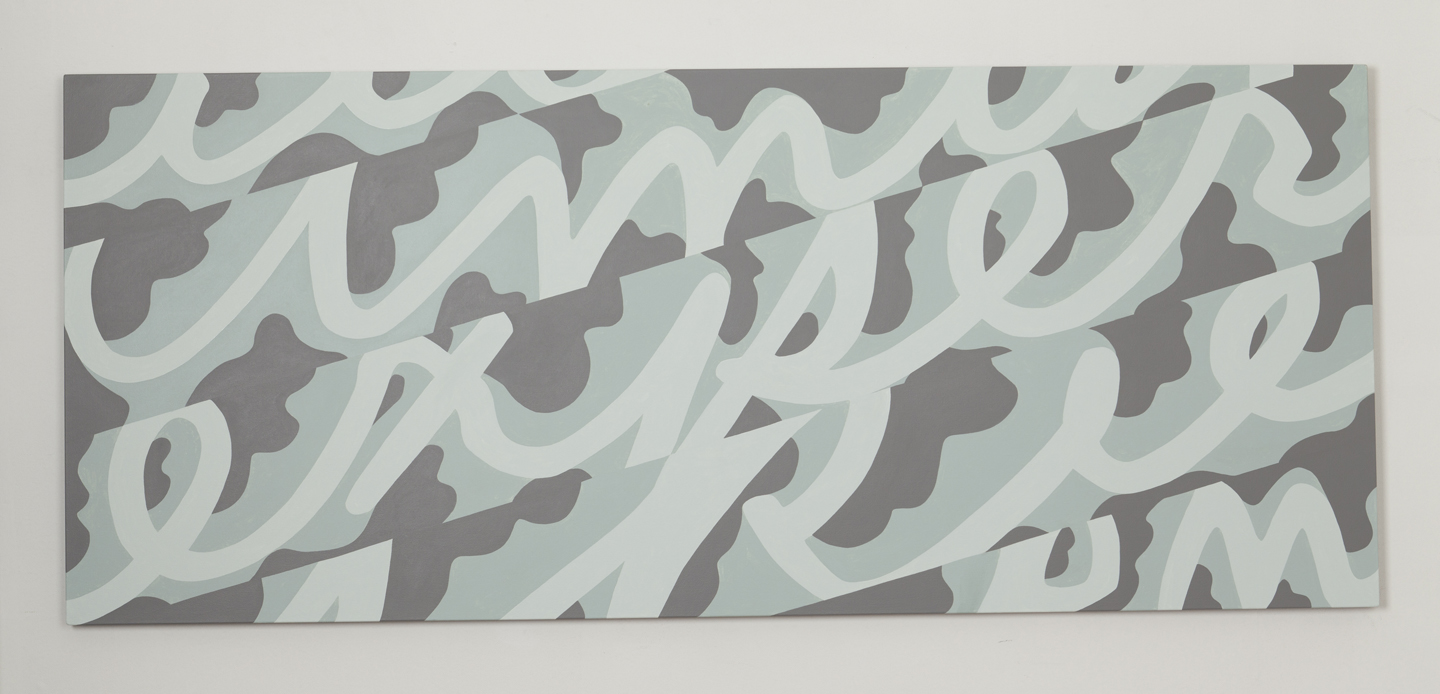

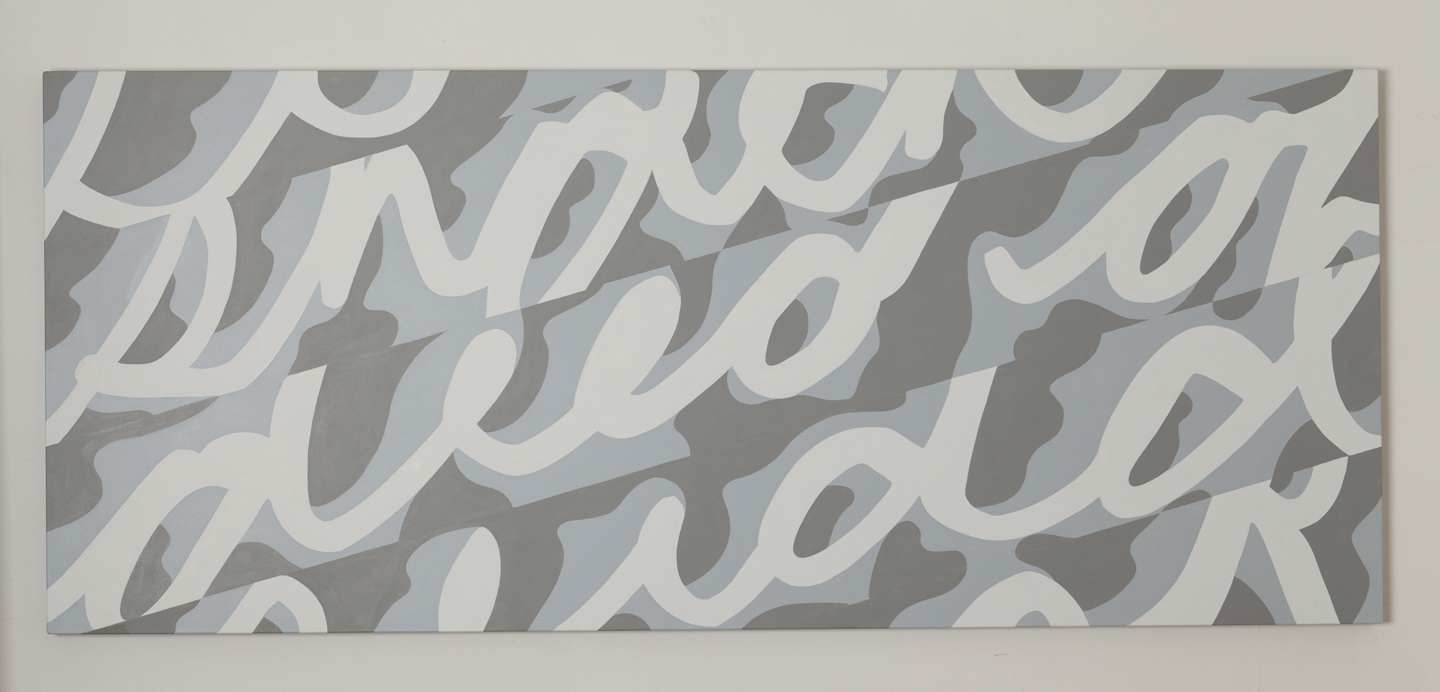

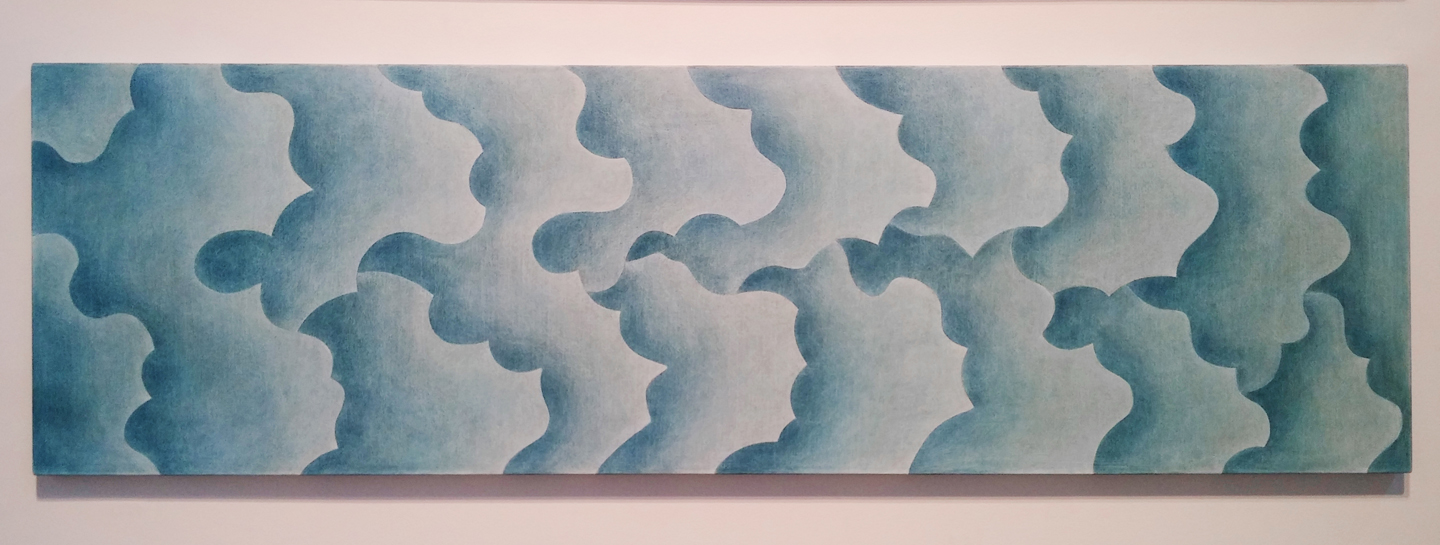

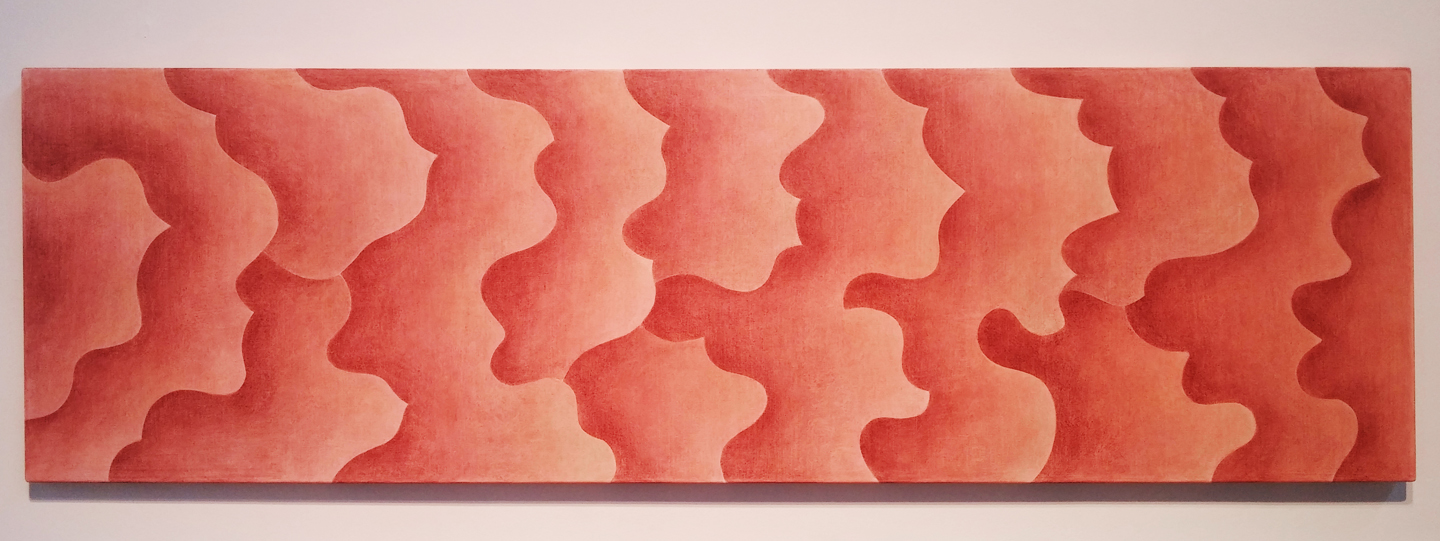

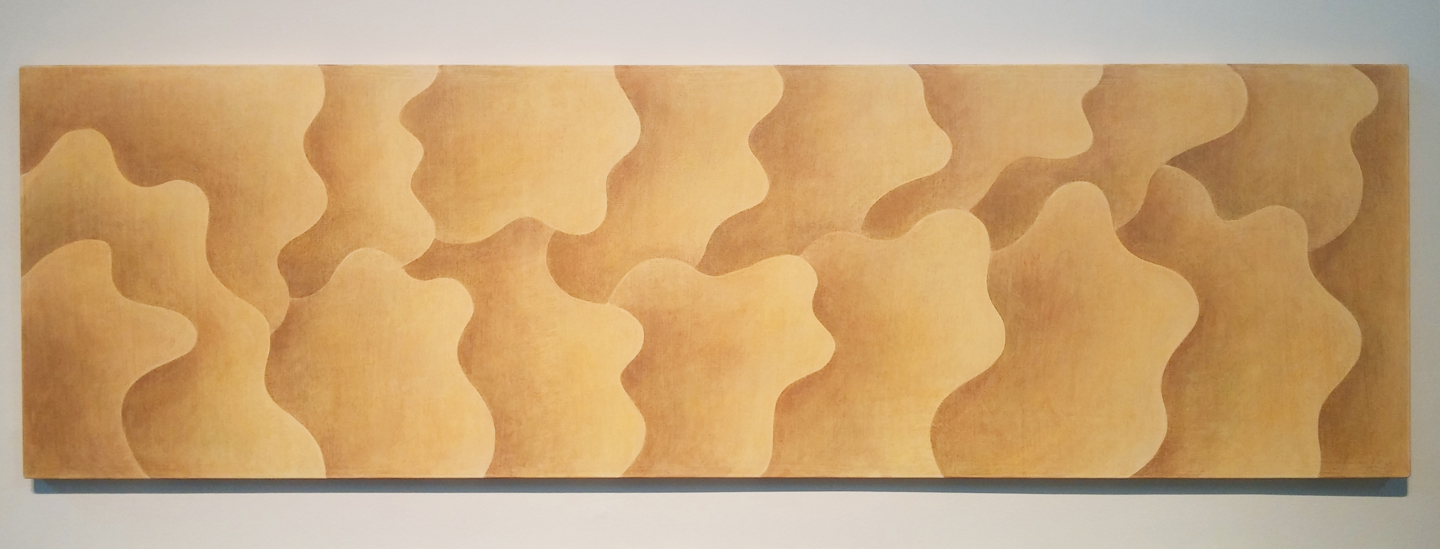

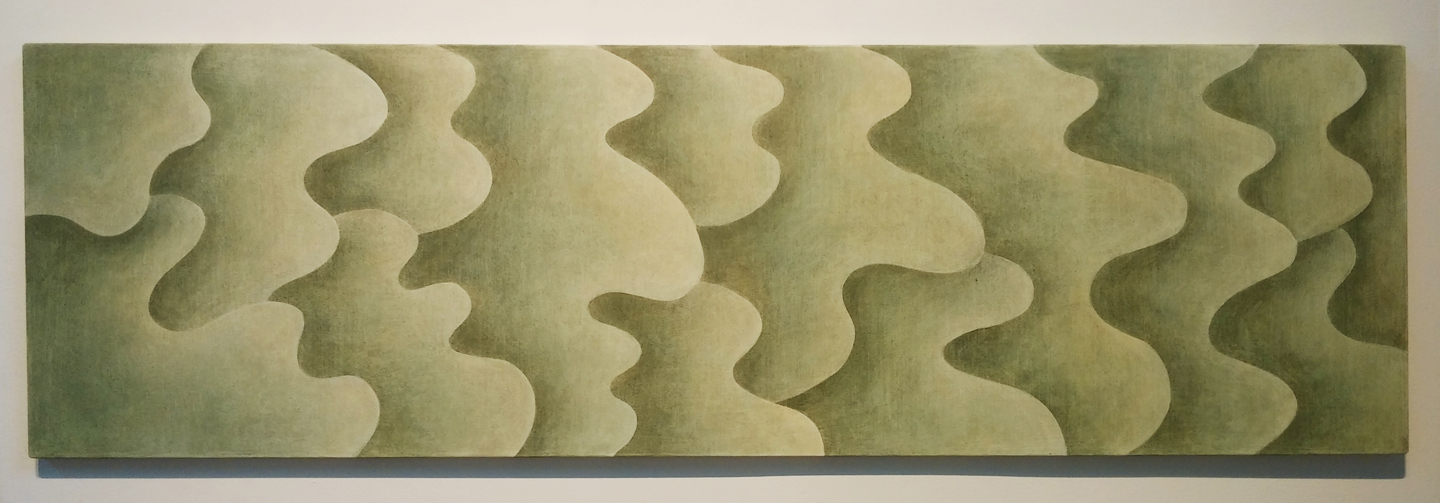

On canvas, the abstracted text has been blown up, twisted, and transformed into a cool polar environment. The diagonal bands of cursive fall off all sides of the painting like glacial cliffs, making it impossible to read the text in sequence. The slivers of sentences have been reproduced in sleek grays and cool blues, trailed by organic shapes that camouflage the already next-to-illegible text. Looking at these elusive shapes, one sees vast snowdrifts built up against the letterforms, or possibly the ominous shadow of ice beneath water, or (more indescribable still) the nebulous clouds that accompany creation and evolution: the gathering of something just on the cusp of solidity (a boy on his way to manhood?).

The paintings are intricately layered – colour, form, and narrative blended to perfect abstraction – but the clues are all there. By gathering pieces of the story like a handful of cards, one can interpret the atmosphere of colours and shapes as they relate to personal experiences, and use memories to flesh out a narrative.

The Polar Explorer painting titled Peary found has even further connections to Fones’ past. In 2008, he created a photo series that featured floating lanterns as they explored Toronto. The lanterns (smiling with all the congeniality a dismembered head can muster) travelled through the City, observing without necessarily understanding, much in the same way the viewer observes Fones’ artwork. In the piece Meteorite Finds, the lanterns discovered three meteorites. Meteorite Finds was based on three actual meteorites that had been revered by a Native tribe in Greenland, which they named The Dog, The Woman, and The Tent. In the late 1800s these meteorites were discovered by none other than the Polar Explorer Robert Peary, who promptly loaded the meteorites onto his boat and brought them back to New York City, where they remain to this day. The painting Peary found is a mere fragment of this history, it’s only upon looking back that we can assemble the full story and realize that what Peary found was the same three meteorites from the floating lanterns travels.

Opening Reception

October 2, 2014 6:00 pm – 9:00 pmArtist Links

Included Artworks