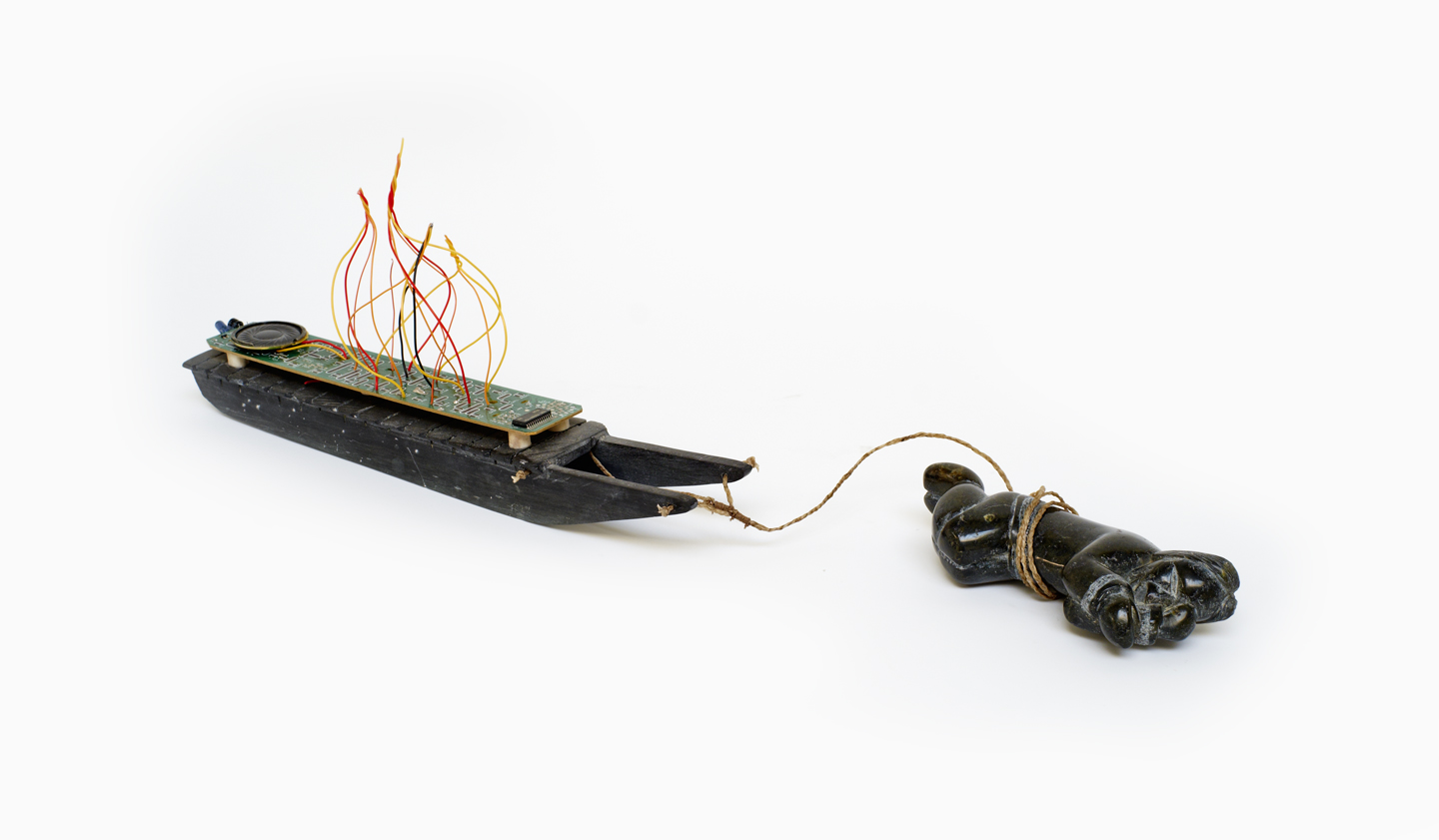

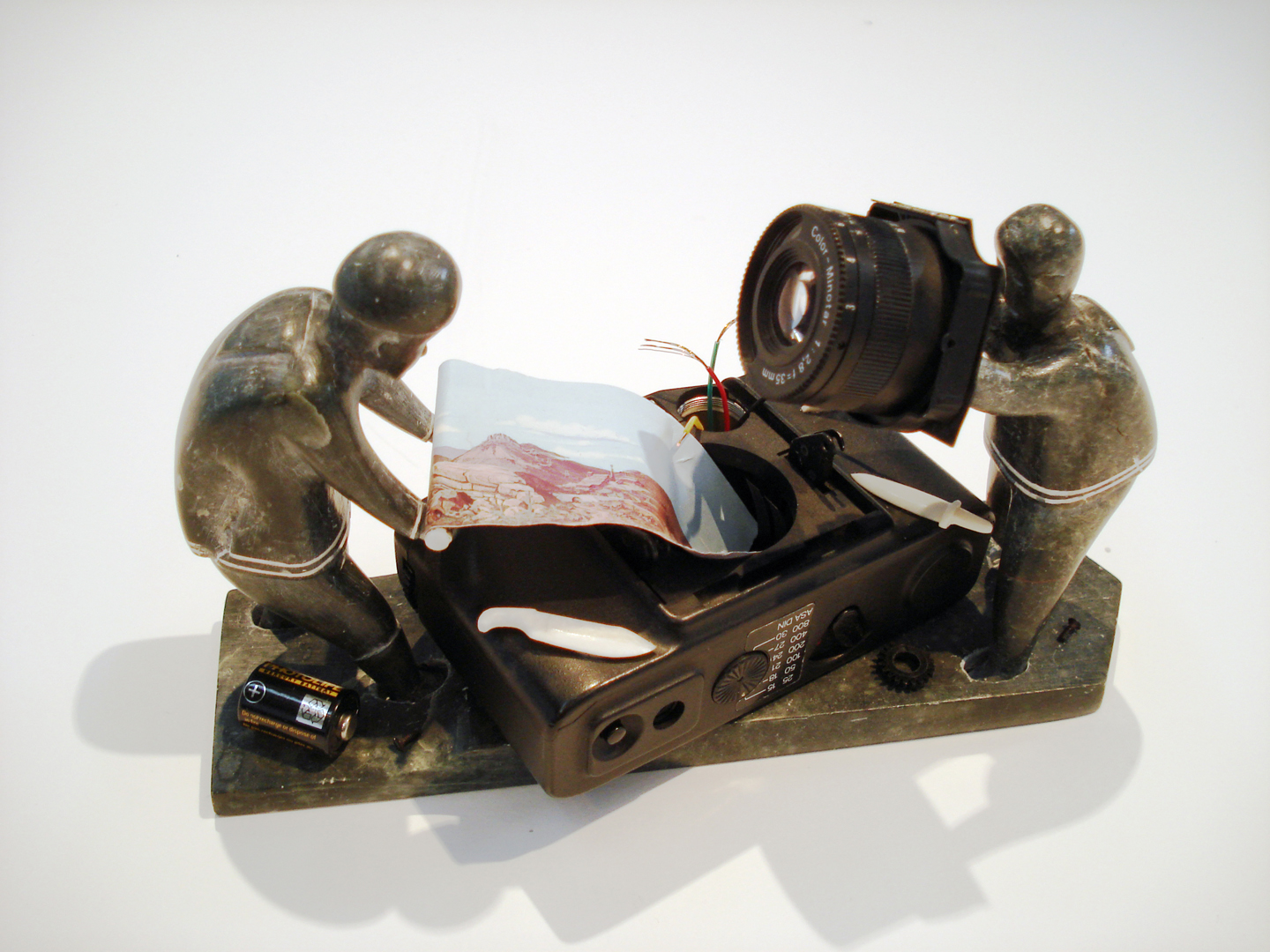

For over 35 years, I’ve served the Inuit art community as the go to restorer of the sculpture. And over those decades I’ve accumulated inventory of damaged and abandoned sculptures, elements, and fragments, and I’ve long mused on how objects of distinction become disposable. It’s a unique position, that of the last repository of the unwanted. So in the spirit of rescue, of reduce, re-use, recycle, I’ve collaged surplus sculpture, consumer electronics and household goods, and invoked autobiography with the inclusion of my long-treasured camera gear in the remix. My interventions contrast actual objects of my material world with the story-telling representations of the Inuit. So why employ Inuit art in this meditation on objecthood? It’s immediately recognizable (as opposed to contemporary art), a signifier of preciousness, and treated to a separate critical discourse. Yet is has always been a hybrid practice – and a practice that has triumphantly exceeded its beginnings as a government economic development project due to the creative spirit of the artists. This installation is meant to recall those storied first exhibitions of sculpture in Montreal in the 1950’s. Why now? The current flowering in First Nations’ art all over this land has produced a confident push-back of dominant consumer culture. In the Arctic in particular, one sees this reversal in the work of sculptors such as Jamasie Pitseolak and Isaacie Etidlooie, and graphics artists such as Annie Pootoogook and Tim Pitseolak. Consider these works as my response to their response – a vehicle to open a conversation.

I’m cognisant of the serious issues of cultural appropriation and copyright and have tried to remix in a way that reflects and honours the art form and artists. This is art as trade goods – these are not sacred objects – yet I’ve been careful even with mythological representations.

Opening Reception

February 1, 2014 2:00 pm – 5:00 pmArtist Links

Included Artworks