Every great technology upheaval has been met with controversy and uncertainty.

Given the ubiquity of text, it is hard to see it as the disruptive technology it once was. But in Socrates’ time, the virtues of the written word were as hotly debated as artificial intelligence and digital technologies are today. Our newest exhibition, Unabridged, takes a long view of the written form, seeking to illuminate these old debates while providing some insight into our present-day predicaments, and our hopes and fears for the future.

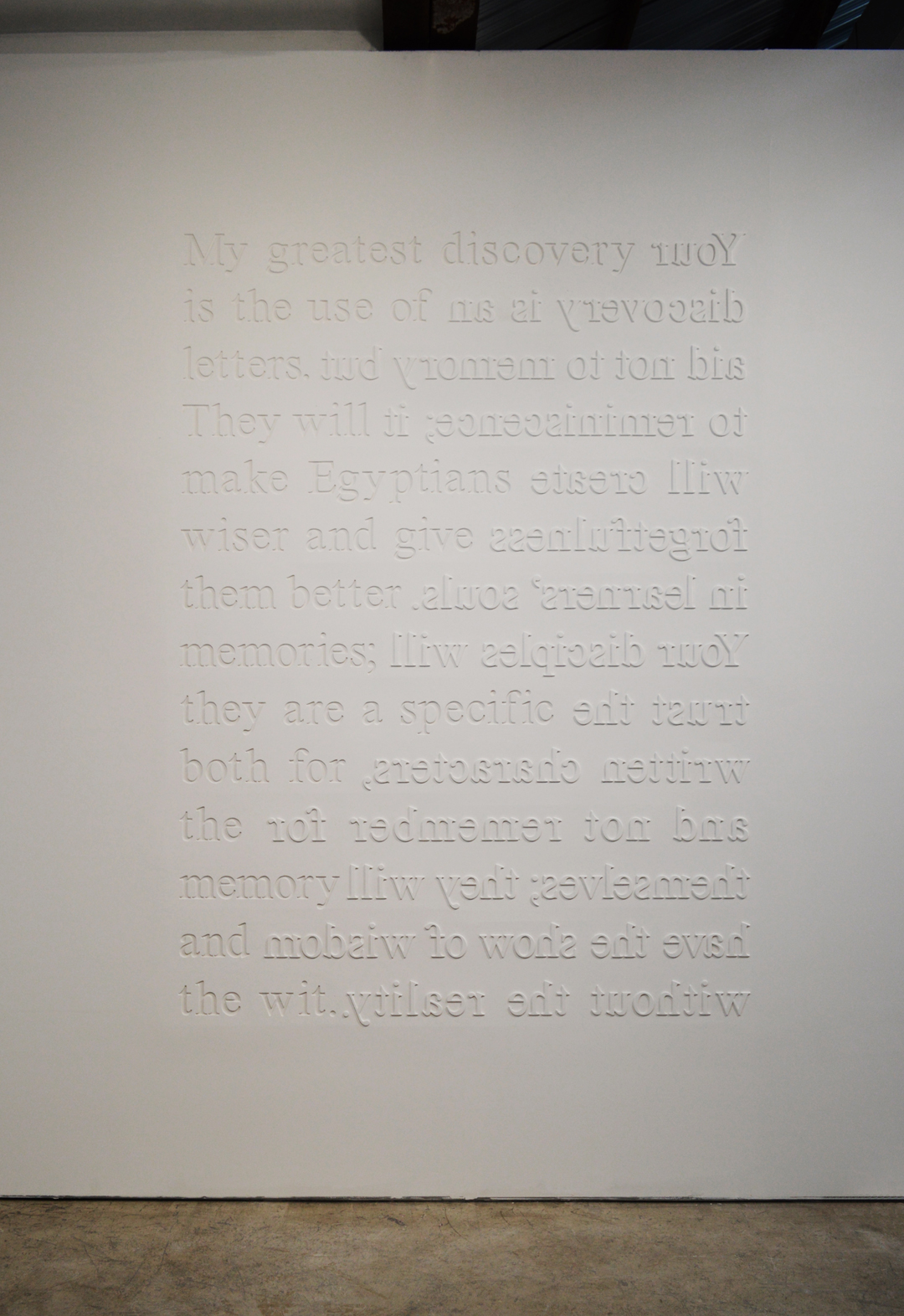

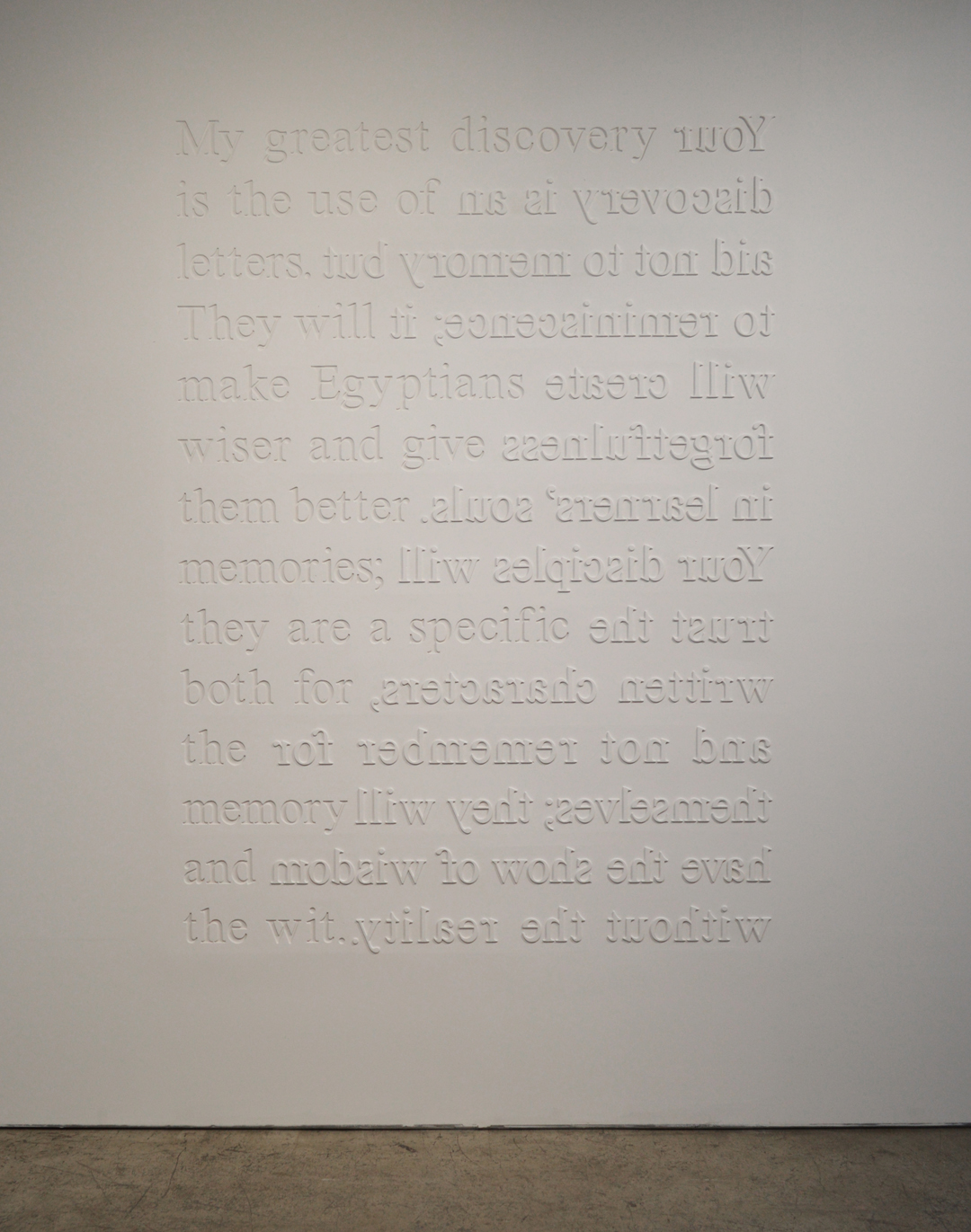

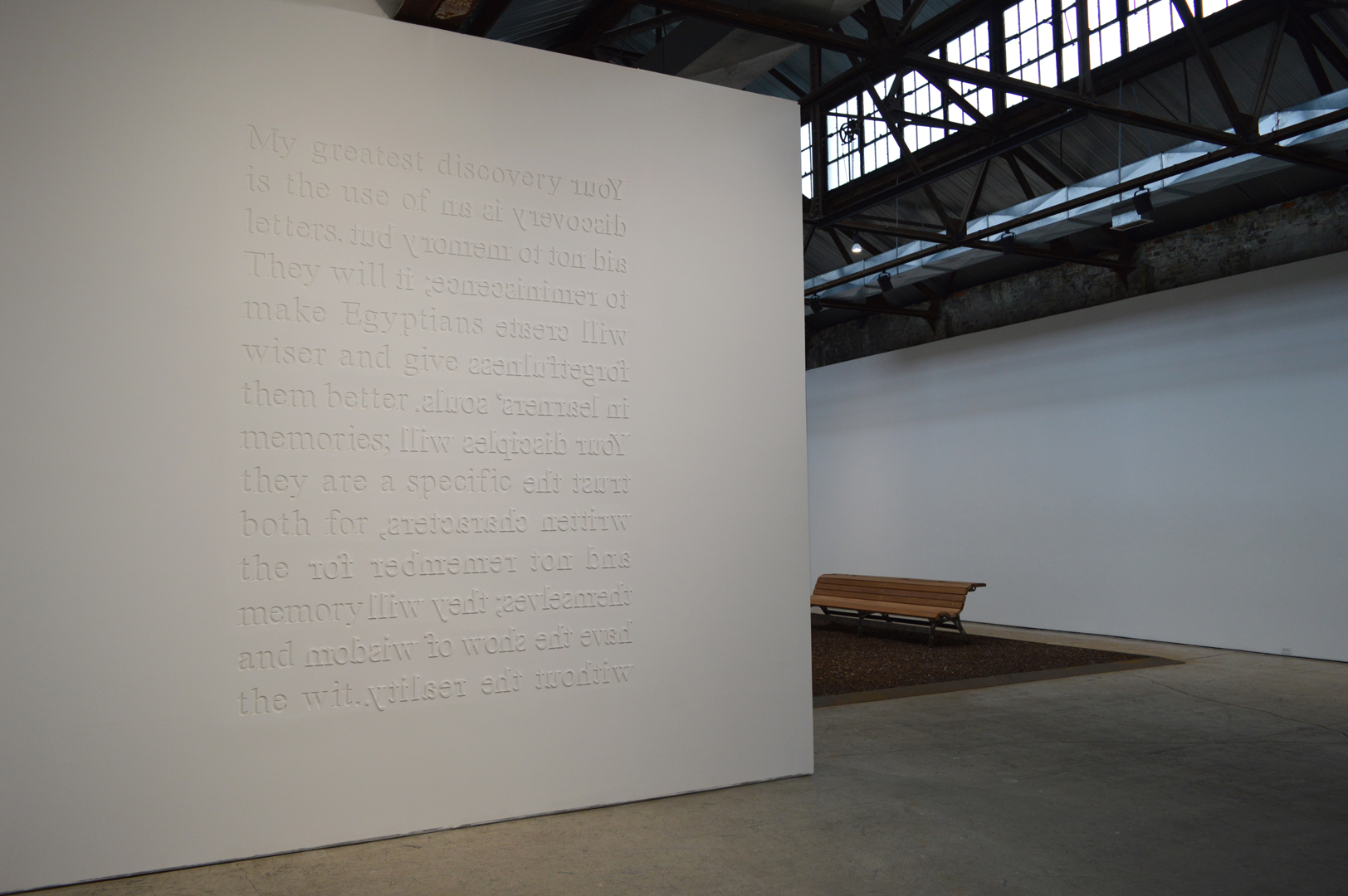

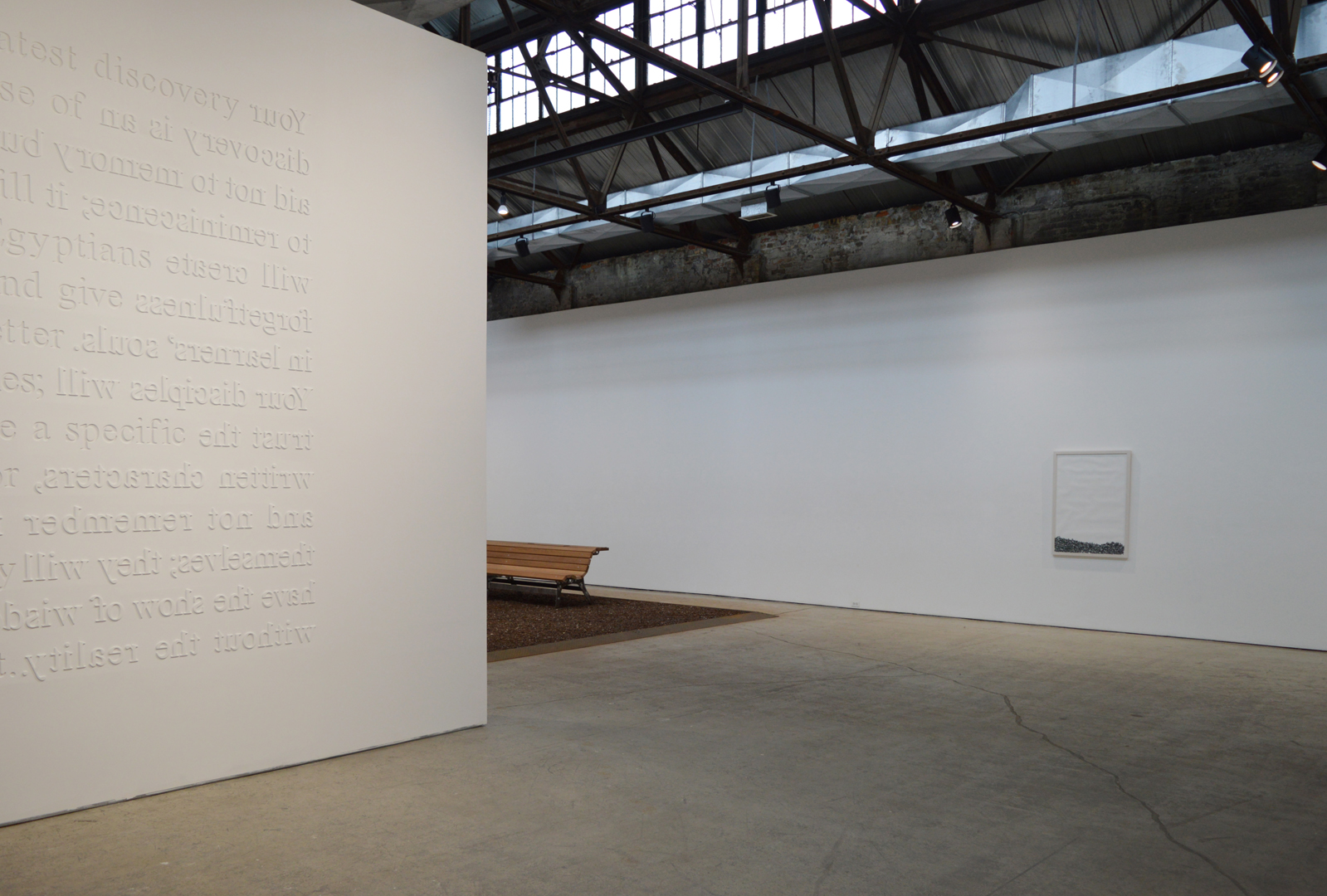

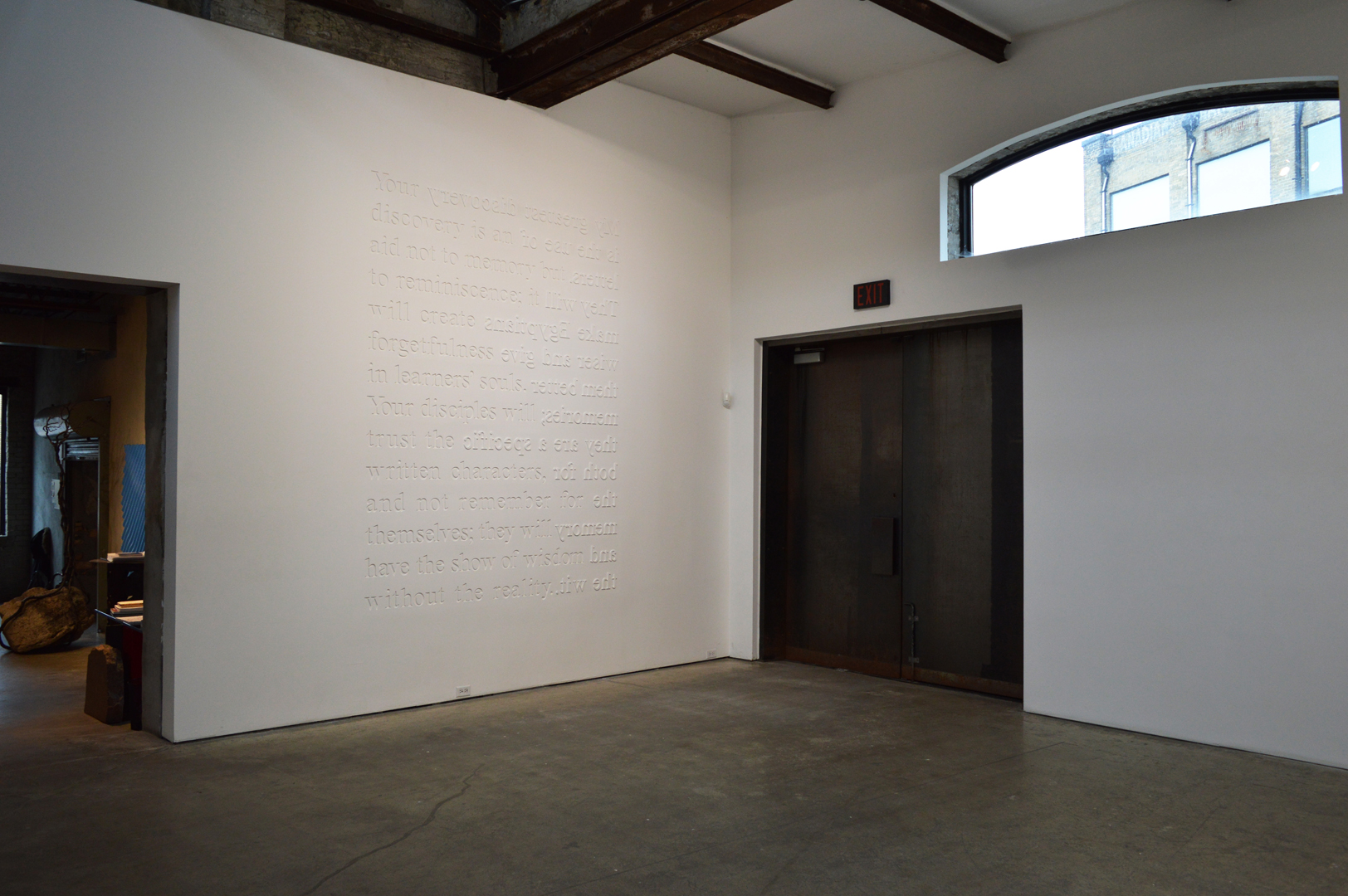

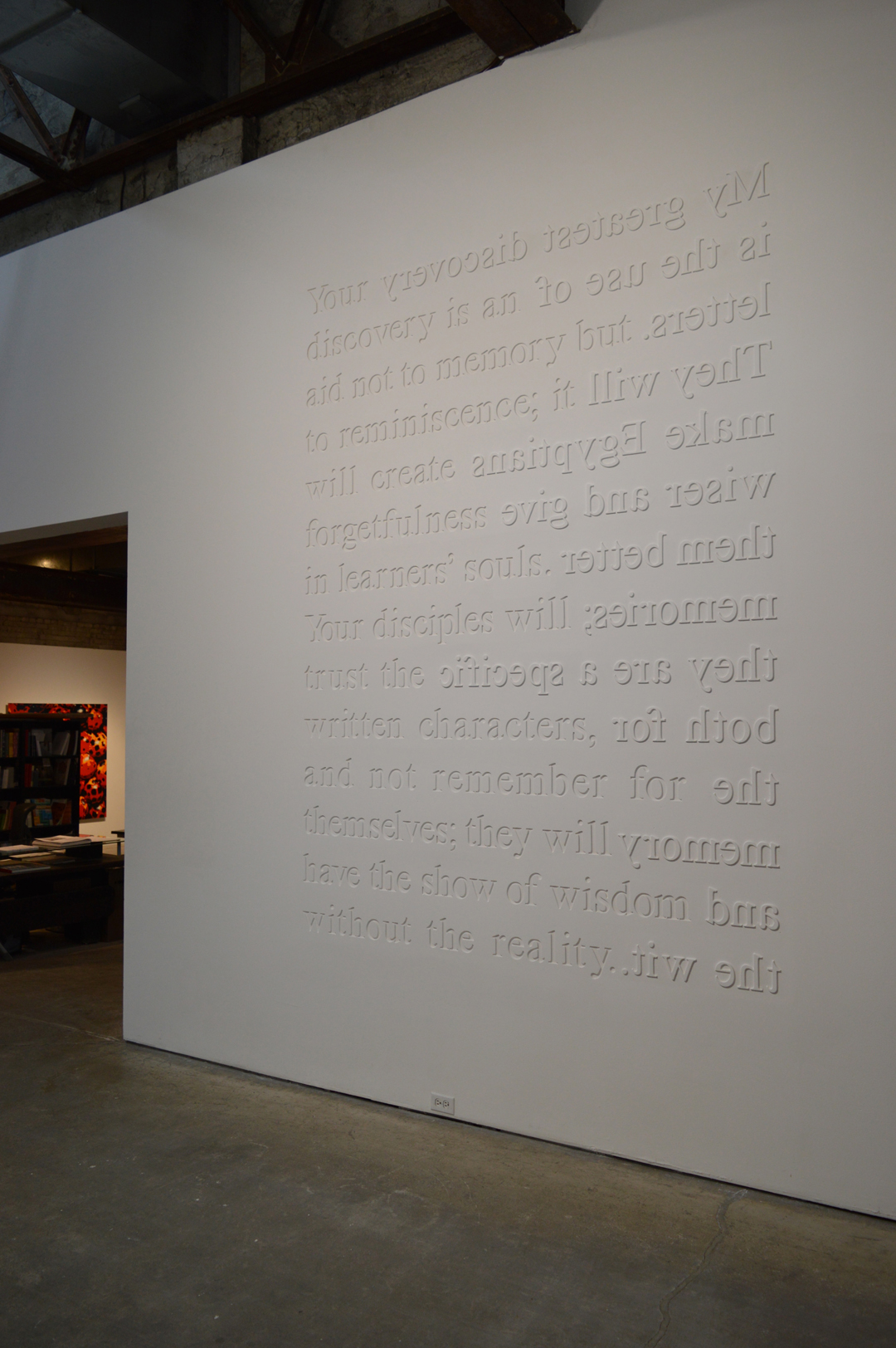

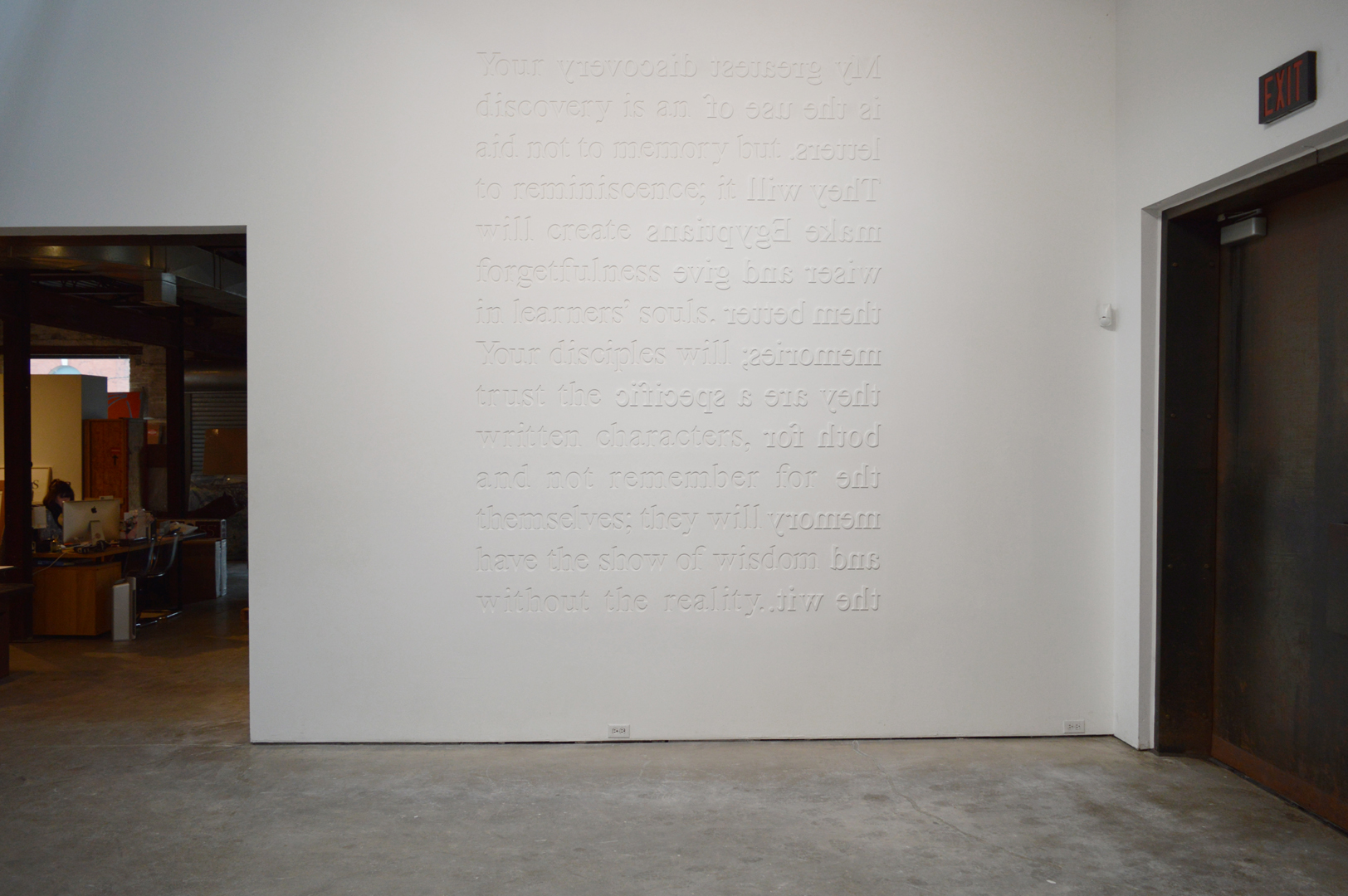

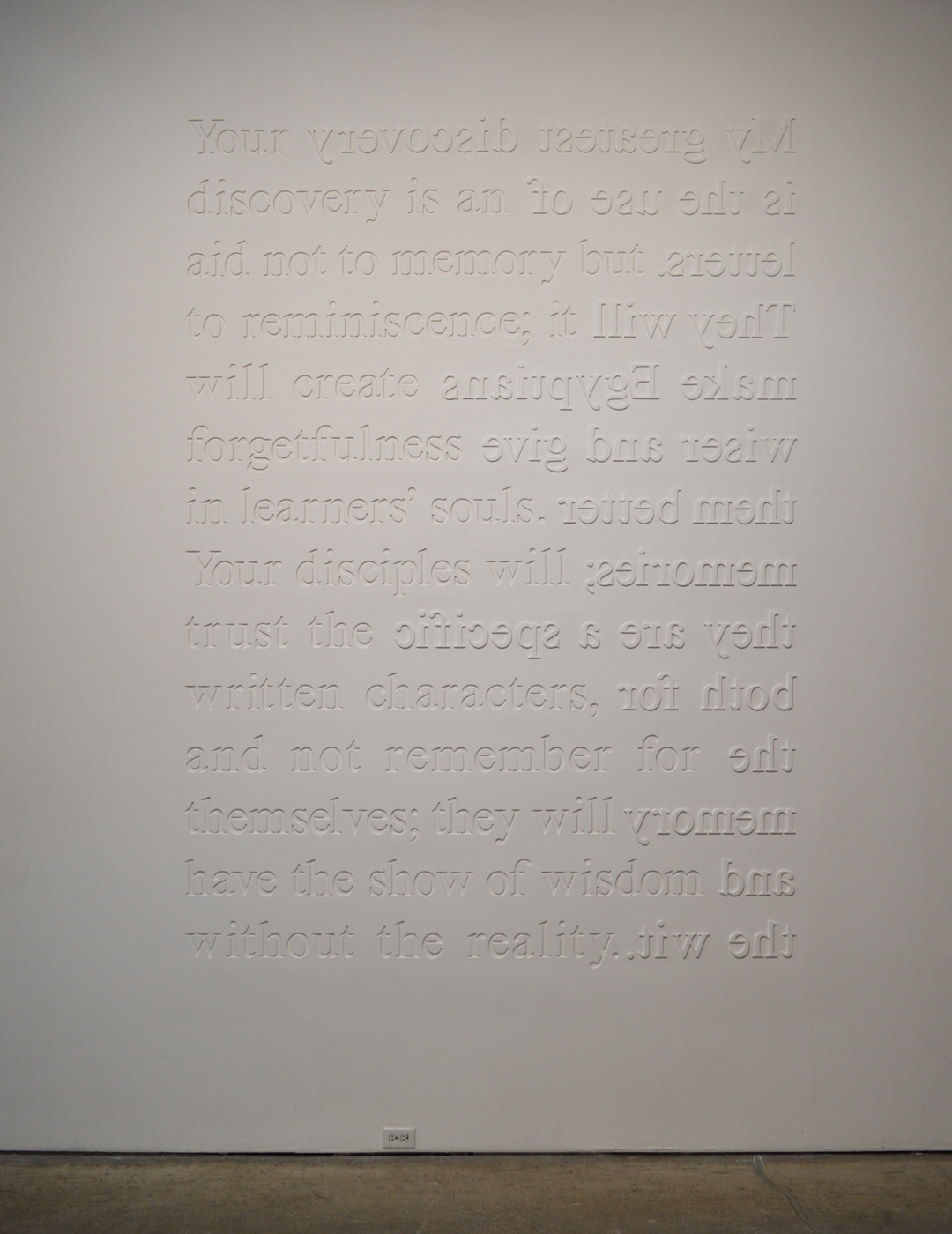

The exhibition opens with Impressions, a full-scale version of a 2005 maquette we conceived as a public art installation for a library or museum. The work features an excerpt from Plato’s Phaedrus, where Plato passes down the teachings of the great orator, Socrates.

In the story, Phaedrus promotes the benefits of written language, arguing that by externalizing knowledge, writing will give men better memories. In counterpoint, Socrates argues that writing will only yield superficial memory, lacking the embodied knowledge that comes with speech: “they will have the show of wisdom without the reality”.

Embedded in opposite facing walls, the artwork consists of two sets of moulds, each the inverse of the other; the dialectic is decipherable only by considering both moulds together. In this way, the work can be read as “thesis-antithesis-synthesis” with the viewer (caught in the middle) embodying the synthesis as an act of performance. Reinterpreting Phaedrus today, the irony of Socrates’ dialogue is that we wouldn’t know about his teachings if Plato hadn’t recorded them in written form. With the help of Gutenberg’s mechanized letterpress, the written word has since become a powerful tool for bureaucracy, institutionalized knowledge, and colonialism that has completely reshaped almost every aspect of modern society, and indeed even history itself. Now structurally embedded in our institutions, text gains its power by simultaneously self-perpetuating and erasing itself as an object of debate.

At the heart of Socrates’ argument for oral history is that you can neither control who will read your written words, nor how they will interpret your ideas. At a technological level, our second installation, titled Rust Garden, moves us through the history of print into our current transformation – where text in its digital form is produced faster and by more people, and shared farther, but is both less permanent and less trusted.

An experiential future of a speculative post-literate society, Rust Garden is a wasteland of discarded text that has been repurposed into a parklike setting. Letterforms that were once combined to tell a particular story take on a new significance when disembodied from their original context. Unhinged from the page and jumbled underfoot as one passes over and into the artwork, the letterforms become filled with personal meaning when visitors pick them up and recombine them into new stories. Some of these stories will be set out in the surrounding area for other passersby to see, while others will be surreptitiously carried off as token keepsakes. What is left jumbled on the ground will continue to rust and decay, eventually decomposing completely.

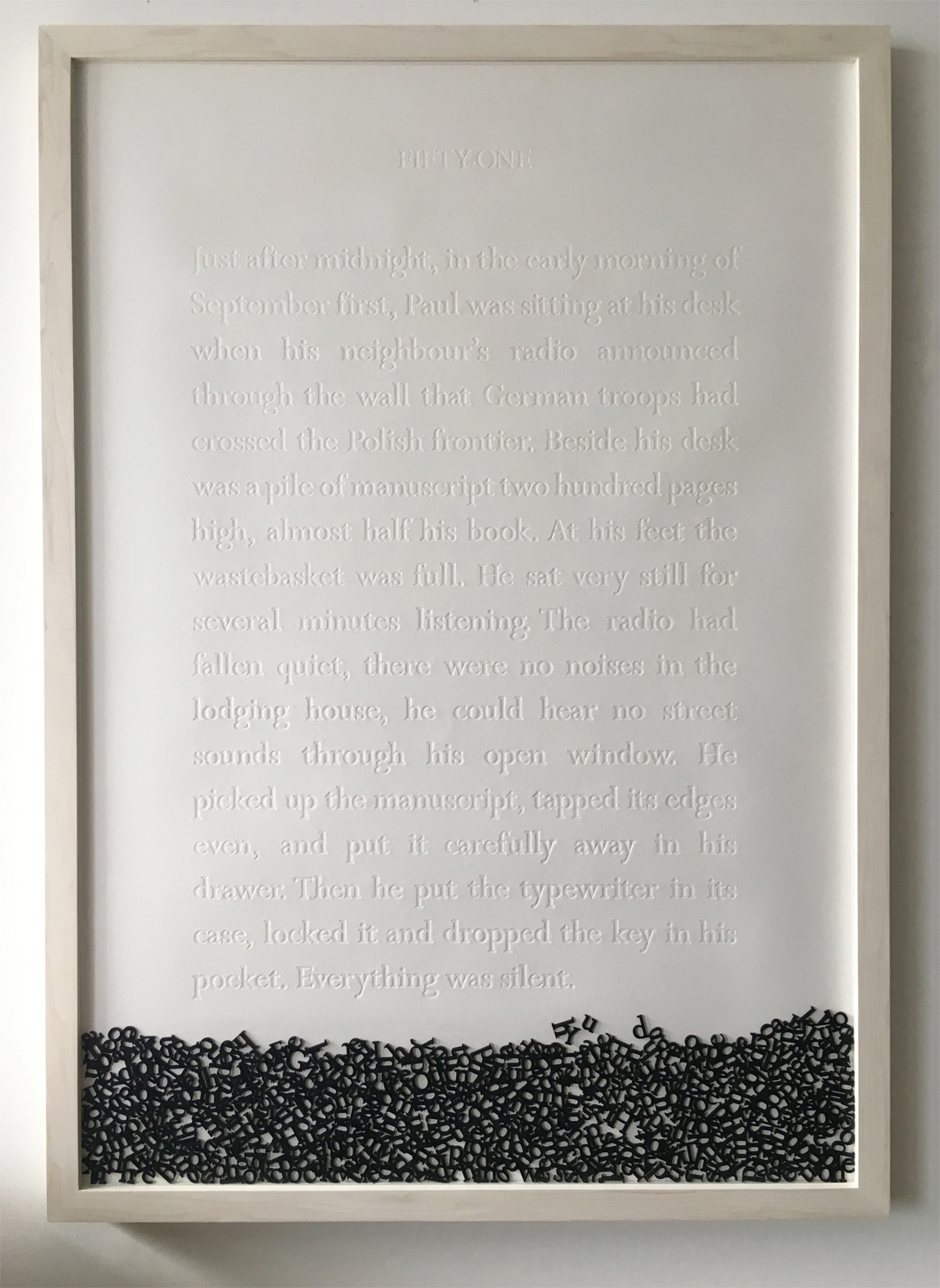

Like our other work, Rust Garden is an ephemeral bridge that straddles multiple places in time, and once again we use a deeply rooted story from our past to help us understand our present-day dilemmas and illuminate possible futures. Conceived as a submission to the Canada Council for the Arts New Chapter program – a one-time grant created to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation – the installation consists of 707,349 letters and glyphs representing every single character from Hugh MacLennan’s 1945 novel Two Solitudes, a CanLit classic hailed as the first novel to explore the idea of “Canadian identity”.

Two Solitudes is a wartime coming of age story about a young man with an English-Canadian mother and a French-Canadian father, who never quite reconciles his mixed-race identity – something many present-day Canadians can relate to. Yet given the reality of our multicultural past and present, one nevertheless can’t help but find discomfort in holding up Two Solitudes as a quintessential representation of the Canadian identity.

Rust Garden asks us to reinterpret Two Solitudes in a contemporary Canadian context that is at once personal and political: to redefine for ourselves what it means to be Canadian today. In keeping with the poem that MacLennan inscribed in the opening pages of his novel — “Love consists in this: that two solitudes protect and touch and greet each other — the work also asks us to listen, hold space for, and acknowledge what “being Canadian” means to others, whether or not this is hopeful, uncomfortable, or painful. In so doing, it attempts to negotiate the tension between Canadian nationalist identity, as it has been narrated for 150 years by Canadian political and cultural institutions, and Canadian national identity, as it emerges collectively among the individuals and cultural communities living within this nation’s borders.

In the broadest sense, it is the dark side of the printed word as an institutional mechanism for cultural erasure that we wish to illuminate, critique, and, hopefully, help transcend with this work. Rust Garden evokes both the decay of modernity and its enduring industrial legacy while also telling a story of repurposing and, in the context of the garden, potential transformation and renewal.

Socrates could not have predicted the mechanized printing press and how this would elevate certain spoken vernaculars into languages of administration that would come to dominate over others. But he feared that our skills for dialogue, and negotiation — and hence our capacity for deep understanding — would be lost if we were to become overly dependent on the written word. If history, colonialism and nationhood are children of the printing press, what stands to be gained or lost in our current great transformation? What stories will we come to tell about ourselves, about others, and our place in the world? How will we tell them?

What conversations and actions are needed now for a truly New Chapter of humanity to begin?

***

We wish to acknowledge the generous support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council, as well as the assistance of family and friends, without whom this project would not have been realized.

[Canada Council New Chapter Logo]; [Ontario Arts Council Logo]

This is one of the 200 exceptional projects funded through the Canada Council for the Arts’ New Chapter program. With this $35M investment, the Council supports the creation and sharing of the arts in communities across Canada.

Ce projet est l’un des 200 projets exceptionnels soutenus par le programme Nouveau chapitre du Conseil des arts du Canada. Avec cet investissement 35 M$, le Conseil des arts appuie la création et le partage des arts au cœur de nos vies et dans l’ensemble du Canada.

Opening Reception

November 7, 2018 2:00 pm – 5:00 pmArtist Links

Included Artworks

artwork detail

artwork detail